Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

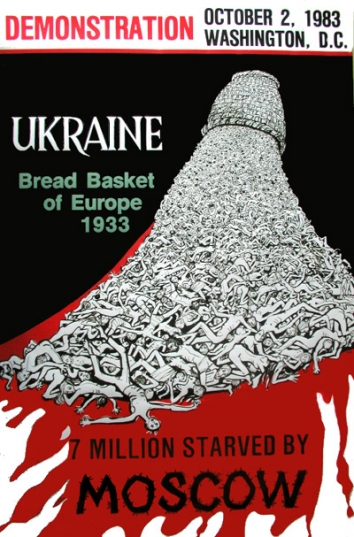

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

What is Ukraine’s economic outlook for 2021?

Anders Aslund, Atlantic Council,

Anders Aslund, Atlantic Council,

Thu, Jan 11, 2021, Wash., D.C.,

One year ago at the beginning of 2020, I wrote that Ukraine’s considerable economic achievements during the previous twelve months were under-appreciated and deserved far greater recognition. I also argued that in 2020, we should look out for a cleansing of the law enforcement agencies, improvements in state administration, and the opening of all kinds of new markets.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk declared five percent GDP growth as the aim for 2020, rising to seven percent annually in the ensuing years. I assessed his goals as sensible. At the time, the general mood was broadly optimistic.

Alas, none of this happened.

Instead, Ukraine’s GDP slumped by about five percent in 2020. The main reason, of course, was the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced the Ukrainian government to close down much of the economy in the second quarter.

The other key reason for this sharp economic downturn was President Zelenskyy’s decision to sack his reformist government in March 2020. He then proceeded to remove all remaining reformers from senior positions in his administration, while failing to launch any fresh reform initiatives. Instead, Zelenskyy’s reloaded cabinet of ministers now resembles a group of random administrators subject to substitution at any moment.

For 2021, a reasonable expectation is that the economy will grow by about five percent, which is just a rebound. This projected growth mirrors the amount the economy contracted last year, and the reasons for this are not entirely rooted in lockdowns. In comparison with other countries, Ukraine has done reasonably well during the coronavirus crisis, but this is not because of the governnment’s economic policies.

A key reason for Ukraine’s relatively solid economic performance in 2020 was the country’s macroeconomic development, which was better than expected. International currency reserves increased to USD 28.5 billion by the end of the year. This was the highest level since 2011, before Viktor Yanukovych began plundering the country.

The growth in currency reserves was possible as Ukraine benefited from a great windfall in its foreign trade. Ukraine’s terms of trade improved significantly in 2020 because prices for primary exports such as agricultural goods, iron ore, and steel all rose, while the price of energy imports fell. This allowed Ukraine to attain a current account surplus equal to four percent of GDP, while it usually has a deficit of about three percent of GDP. This one-time effect is unlikely to be repeated.

Other reasons for Ukraine’s macroeconomic stability include the fact that international tourism almost ceased during 2020. This had a positive impact on the economy because Ukrainians typically spend much more abroad than the country receives from incoming tourists. Ukraine closed restaurants, hotels, and bars for extended periods last year, but these services employ a smaller share of the labor force in Ukraine than elsewhere. In short, Ukraine experienced many of the most common negative economic consequences from the pandemic, but the impact was less severe than in other countries.

The main institution behind Ukraine’s economic achievements during the past six years has been the National Bank. It has driven down inflation through a responsible monetary policy and closed more than one hundred crooked banks as part of a comprehensive reform. Thanks to these measures, the exchange rate of the hryvnia currency has stabilized and even appreciated in 2019.

Unfortunately, no good deed goes unpunished. While most foreign economic observers regard the post-2014 role of the National Bank as the greatest achievement of Ukraine’s entire reforms agenda, the Zelenskyy administration chose to treat it as a mistake. During the early months of 2020, the rent-seeking Ukrainian elite cried out for lower interest rates, lower exchange rates, and higher inflation, so that they could earn more by doing less. Unfortunately, the voice of the people, whose dollar wages were stagnating, was ignored.

Strangely, the main aim of the government became to castrate the National Bank, the country’s greatest success story. It did so by ousting the winning National Bank team. However, the International Monetary Fund did manage to persuade the Ukrainian government not to return the bankrupted banks to their previous owners, and succeeded in convincing the authorities to maintain a strict monetary policy.

In 2020, Ukraine found itself in a complex dilemma regarding green tariffs. Under Yanukovych, Ukraine was one of many other European countries to introduce high green tariffs in order to stimulate investment in wind and solar energy. This succeeded in attracting substantial foreign direct investment to Ukraine. In 2020, however, the Ukrainian government did not know what to do with these high tariffs. It waited for too long, leaving state arrears of about USD 1 billion. Many arguments are possible about the rights or wrongs of Ukraine’s electricity price regulations, but arrears are never the correct option. The government’s treatment of these arrears has deterred foreigners from investing in Ukraine altogether.

Looking ahead, Ukraine’s worst economic problem remains the absence of property rights, which continues to hinder investment of any kind. Judicial reform was supposed to be at the top of the Zelenskyy government’s agenda in 2019, but since the sacking of the previous prosecutor general in March 2020, everything has gone backwards. During the second half of 2020, the allegedly corrupt Constitutional Court ruthlessly dismantled the whole framework of anti-corruption institutions established since 2014. President Zelenskyy rightly protested, but he has yet to demonstrate that he can actually do anything to counter the outrageous actions of the Constitutional Court.

Ukraine’s rule of law shortcomings continue to have an unwelcome impact throughout the economy. In spring 2020, the Ukrainian parliament adopted a long-awaited land reform bill, paving the way for an agricultural land market. Will this reform prove effective without credible property rights? Many investors remain unconvinced. Instead, foreigners continue to purchase Ukrainian bonds happily. This enthusiasm reflects the high yields Ukraine must pay due to legal uncertainty.

As we move into 2021, the country’s macroeconomic stability appears strong, but few dare to invest in Ukraine. Without judicial reform or an increase in investment, there is little reason to expect any economic growth beyond the gains arising from the anticipated post-coronavirus rebound.

Anders Åslund is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. His most recent book is “Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy.”

LINK: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/what-is-ukraines-economic-outlook-for-2021/