Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

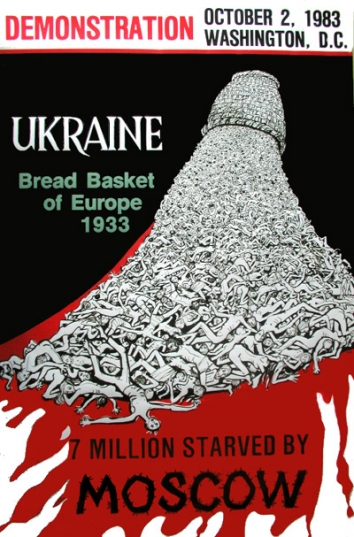

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman: a solution to Ukraine's rule of law problems by Bate C. Toms, Chairman of the British Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce and Managing Partner of the Law Offices of B. C. Toms & Co

Business Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine,

Business Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine,

May 20, Thu, 2020

Ukraine is in need of a fresh approach to judicial reform in order to overcome deep-seated problems within the country’s legal system. The creation of a Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman should be the best way forward

Bate C. Toms

Monday, 17 May 2021 20:02

The British Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce (BUCC) seeks to solve the most important rule of law problem for Ukrainian courts. To protect existing investors and encourage new investment in Ukraine, the BUCC proposes the creation of a Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman.

So far, the various initiatives for court reform in Ukraine have not succeeded. There continue to be numerous clearly baseless decisions by Ukrainian courts, in particular when investors have tried to defend their interests against illegal corporate raiding and other fraud. This is discouraging further investment in Ukraine. In response, there are renewed calls for another court reorganisation, however, merely reorganising court structures and replacing judges yet again is not likely to change the situation that is based, in part, on long established expectations for corruption by some of those involved in the judicial system.

It is time for a different approach to address the problems with Ukrainian courts.

Proposed Judicial Ombudsman

What is needed to better protect litigants in Ukraine is true systemic reform that addresses the content of judicial decisions, and imposes some cost for clearly wrongful behaviour by judges harming litigants. Most Ukrainians, as well as foreign investors, generally perceive the courts to be highly corrupted, with many important cases being resolved through corruption.

The BUCC’s proposed solution to deter wrongful judicial behaviour is to create a Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman to respond to the critical problem facilitating improper court decisions in Ukraine, which is the total absence of any independent outside review of what courts actually do. Instead, the Ukrainian judiciary has become a closed system whose misbehaviour is wholly immune from any genuine outside criticism or quality control.

The Judicial Ombudsman is a “magic bullet” solution that would address this cause of the problems and thereby fundamentally improve the Ukrainian judicial system. By creating a Judicial Ombudsman, similar to the “Justice Ombudsman” used in Sweden, to review decisions that are claimed to have no proper legal basis under applicable law, litigants could be much better protected from the corruption that fraudsters and others have used in order to judicially dispossess investors in Ukraine, that has resulted in so many bilateral investment treaty (“BIT”) arbitrations over clearly wrongful Ukrainian court decisions.

In the 1800s, Swedish courts were also perceived as being among the more corrupt in Europe, but Sweden’s creation of a Justice Ombudsman put their courts onto a completely different course. The Swedish Justice Ombudsman cannot revise decisions or send cases back for re-hearings, but this ombudsman can criminally prosecute judges for the commission of crimes, including for neglect of duty if they act grossly improperly to decide a case. Instead of prosecuting judges, however, ordinarily it is enough for the Justice Ombudsman to provide a suggestion or reprimand, which Swedish judges usually follow rather than force a prosecution to be brought.

The Justice Ombudsman’s recommendations and reprimands are generally technically written in line with the best Western judicial decisions. For this reason also, they are ordinarily fully implemented by judges voluntarily. On the rare occasions when this does not happen, the Swedish judges involved may be prosecuted, and ultimately removed from office, among other penalties, for breach of their judicial duty.

Ukraine should now use such a Judicial Ombudsman to develop, as Sweden has successfully done, into a model country for both justice and commerce, which are, of course, linked.

The proposed Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman suggested by this article should be based on the standards that are generally applied under Ukraine’s BITs. For example, if a court decision constitutes a “denial of justice”, meaning a judicial decision for which there is no genuine legal basis, the judges responsible could be held accountable.

Under Article 126 of the Ukrainian Constitution, a judge may be dismissed for significant disciplinary misconduct, gross or systematic neglect of duties incompatible with the status of a judge. This should be applied by a criminal law statute to any material failure to observe the Ukrainian judicial oath of office that requires each judge to “objectively, impersonally, impartially, independently and fairly administer justice, complying only with the law…” (“fairly” should be defined to mean acting based on applicable law). The proposed Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman, by applying such a standard to evaluate decisions by judges, could obtain revisions to judgements for which there is no reasonable legal basis, or else prosecute the judges involved and seek their removal.

The possibility of such Ombudsman review should quickly cause court judgements to be rendered much more carefully. Where some clearly wrongful court judgements continue to be rendered, the Judicial Ombudsman’s decisions should result in the removal of the responsible judges who persist in misbehaviour, thereby improving the Ukrainian judiciary over time. This process is preferable to lustration and replacement of judges for reasons not connected to their actual judicial performance.

Recommendations for Implementation

The following three approaches could be used, in stages, to implement this Judicial Ombudsman proposal. To begin quickly, in the first stage, the Judicial Ombudsman could be created initially as an advisory body to review allegations by investors and others of judicial abuse by courts in their consideration of claims. As suggested above, the criteria for judging court judgments could be based on that applied under most Ukrainian BITs for investor arbitrations.

We would recommend that, to be appointed, the Judicial Ombudsman should be nominated by the joint action of a group representing investors composed of chambers of commerce and business associations representing the principal foreign countries from which investments come in Ukraine as well as those representing Ukrainian investors, possibly acting with certain other Ukrainian non-governmental organizations as many be decided; and an appropriate governmental or parliamentary body, like the Ukrainian Parliament’s Committee on Legal Policy. This nominee should then be subject to approval by the President or Parliament.

This Judicial Ombudsman could provide independent legal opinions in response to complaints from investors or other litigants. Based on such an opinion, a foreign investor and his government would not have to face the typical response by the Ukrainian Government to complaints about abuses of justice by Ukrainian courts resulting in a loss of rights or property, at least prior to an eventual BIT arbitration award, which is that the Ukrainian Government explains that it is not made up of lawyers and therefore cannot consider an investor’s legal complaint over a judicial decision because there is no independent evaluation of the decision that they can also consider. In other words, Ukrainian governments have typically alleged that the complaints against wrongful Ukrainian judicial decisions are merely claims by interested investors or other litigants presenting their biased viewpoints, no matter how blatant the injustices committed by the courts.

By contract, the Ukrainian Government should be able to take into account an independent opinion from a respected Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman in order to address the complaints of foreign and domestic investors and other litigants, and act to remedy obvious wrongs caused by judicial misconduct, instead of forcing investors and other litigants to spend huge amounts over many years of litigation and then in BIT arbitrations seeking justice.

The government could instead, based on its evaluation of the opinions of the Judicial Ombudsman finding clearly wrongful judicial misbehaviour by judges, compensate investors and other litigants for their losses due to such misbehaviour. The Ukrainian government could also, based on the Judicial Ombudsman’s opinions, appear in court as well as in arbitral proceedings, with briefs supporting investors. In addition, the Judicial Ombudsman could apply to prosecutors with recommendations for the prosecution of the judges involved.

The High Council of Justice could likewise, based on the legal opinions of the Judicial Ombudsman, consider judicial actions and remove judges who materially violate their oath of office, which should qualify under Article 126 of the Ukrainian Constitution as a gross neglect of duty. While currently theoretically possible, almost no judges have ever been removed, despite evidence of egregious behaviour being presented against a number of judges. If rendering judgments that constitute denials of justice and other breaches of the judicial oath are made crimes by new legislation, as recommended below, then Ukrainian prosecutors, along with the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) and the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office, could also, based on the recommendations of the Judicial Ombudsman in legal opinions, bring prosecutions against the judges responsible for abuse of their judicial oath.

On this basis, potential and existing investors in Ukraine should feel much more secure and be encouraged to proceed with investments, improving the economy of Ukraine for the benefit of all. Such advisory opinions of the Judicial Ombudsman would thereby, compared to the BIT process, provide a relatively quick and inexpensive way to help protect investors and, by weeding out misbehaving judges, improve the composition of the judiciary over time. Even if such a Judicial Ombudsman’s opinion is not acted upon by the Ukrainian Government or others, it should be given great weight in any subsequent BIT proceedings by clearly evidencing an intentional failure of Ukraine’s legal system properly control itself.

Ombudsman as Special Prosecutor

The second stage, or alternative, for constituting the proposed Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman would be to base it more strictly on the Swedish Justice Ombudsman model, by making the Ombudsman a special prosecutor who could directly prosecute judges that do not implement the Ombudsman’s opinions finding misbehaviour. This would address the risk that the Ukrainian Government may not voluntarily follow a Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman’s opinions.

A special Act of Parliament would be needed to define the scope of the Judicial Ombudsman’s powers to prosecute judges for improper decisions that violate criminal laws (pursuant to Article 126 of the Ukrainian Constitution, judges may be prosecuted for crimes). New crimes for wrongful judicial action, such as by making the material breach by a judge of his or her oath of office a crime, need to be statutorily defined for this purpose, as is further explained below.

Thus, the proposed Judicial Ombudsman could be given the power by statute to prosecute judges at any judicial level for any decision determined to constitute a denial of justice or other material breach of their judicial oath. Such a successful prosecution should lead to the lustration of the judges involved for cause. The Judicial Ombudsman would thereby provide for relatively quick review of a denial of justice decision at any judicial level, with the opportunity for the judges responsible either to then revoke their improper action or else be prosecuted and removed while leaving revision of the decision to other judges.

Such a Judicial Ombudsman acting as a prosecutor would not usurp any judicial functions – the Ombudsman would not function like another court deciding cases. The Ombudsman would instead provide an independent outside review of the legal basis for a court judgment. Where the judgment clearly lacks any proper legal basis, a common problem in Ukrainian courts, litigants could ask the Ombudsman to quickly evaluate the court’s decision and act appropriately.

Likewise, new civil laws need to be adopted to provide for Ukraine to quickly compensate the victims of such clearly wrongful judgements by Ukrainian courts, in response to the opinions of the Judicial Ombudsman, for example where this opinion is confirmed by the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine. Victims should not be obliged to litigate such cases through until a final BIT arbitration, which can take many years and often proves to be much more expensive for all sides than should be the case, as well as very damaging to Ukraine’s reputation as good investment destination. Not remedying such improper judicial actions deters investment and seriously harms Ukraine’s economy.

Prosecuting Judges

Turning to the criminal law legal standard for prosecuting judges for clearly wrongful misbehaviour in violation of their oath of office, the Ukrainian Parliament did try to address such judicial corruption by adopting, on 5 April 2001, Article 375 of the Criminal Code. Article 375 provided that “the delivery of a knowingly unfair sentence, judgment, ruling or order by a judge shall be punishable by restraint of liberty for a term up to five years, or imprisonment for a term of two to five years”. Article 375 also stipulated that where such actions caused any grave consequences, or were committed for mercenary motives or for any other personal benefit, imprisonment can be for a term of five to eight years.

Unfortunately, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, in a poorly worded decision on 11 June 2020, ruled Article 375 to be unconstitutional because the “unjust” criterion was deemed to be too uncertain. It disallowed Article 375 merely because there was a possible interpretation that could mean that this statute could be applied in an unconstitutional manner. Instead, the Constitutional Court should have interpreted this law in such a way that it would be constitutional if there is a reasonable way to apply it consistent with constitutional principles, which there was.

The standard under Article 375 for judges to be found to reach a “knowingly unjust” decision would appear to be a high one, and should not be construed to be necessarily overly vague, where “unjust” is read to mean acting contrary to law, including for a judge to violate his or her judicial oath, and “knowingly” is interpreted to require evidence of actual intent to so act contrary to law. This is not a vague standard, but rather too high a standard to help effectively control misbehavior in Ukrainian courts, as is the case for the crime of bribery that requires catching a judge guilty of taking a bribe “red-handed in the act”. It would presumably be equally difficult to catch a judge admitting to knowingly acting contrary to law to wrongfully decide a case.

By contrast, based on the actual wording of a baseless judicial decision, one can confirm a judge’s violation of his or her judicial oath. It should be enough to apply the standard for arbitration under BITs to so evaluate judicial decisions, so that a “denial of justice” decision that is clearly unsubstantiated as a matter of law should result in criminal liability for the judge involved based on the improper activity, just as a crime is committed when a person negligently kills another or causes serious consequences from reckless driving. The principle for such cases is that liability for such grossly wrongful behavior should arise from the commission of the wrongful act that constitutes a crime, without the need to prove with evidence that the actor actually knowingly intended to act wrongfully. Judges have important professional duties that should result in criminal liability for their decisions if clearly wrongfully performed so as to constitute denials of justice.

This solution is to adopt new criminal statutes to replace the former Article 375 in order to allow for the punishment of those judges who, presumably for corrupt reasons, render judgments that have no genuine legal basis. For this purpose, the Judicial Ombudsman should be empowered by statute to act as a prosecutor, to enforce criminal law judicial standards by bringing prosecution to discipline judges in Ukrainian courts, including in the new High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine.

Judicial Ombudsman as Official Expert

A third alternative approach, due to the severity of the rule of law problem in Ukraine, could be to add further powers for the Judicial Ombudsman to function alternatively as an expert adviser for courts in Ukraine, up to the Supreme Court, to advise on sending cases, decided by a court judgement that constitutes a denial of justice, back for an immediate re-hearing.

The Judicial Ombudsman might also be given such a power to intervene directly, in response to complaints by litigants, and cause such clearly wrongful court decisions to be sent back for a re-hearing, and to freeze enforcement of wrongful decisions pending their re-hearings, though such an approach would need an amendment to the Ukrainian Constitution. This would go beyond the prosecutorial approach used in Sweden, in order to better ensure protection of investors from court abuse in the especially difficult judicial situation in Ukraine. The proposal would not thereby turn the Ombudsman into an additional court deciding cases as such, but merely give the Ombudsman a method for requiring a quick reconsideration by a Ukrainian court, ideally by different judges, before the investor or other litigant concerned is more seriously harmed.

Selection Criteria

For the proposal to work, the Judicial Ombudsman needs to be someone universally respected as being independent, incorruptible and impartial and having the highest level of legal expertise and competence. As for the Ukrainian Business Ombudsman, the appointee might be an eminent foreign legal authority (like the former judges and other legal experts typically appointed to BIT arbitration tribunals), which should help, in particular, to restore foreign investor confidence in Ukraine’s courts.

The aim is to protect all litigants in Ukraine equally, rather than to create a two-tier judicial system where only foreign investors are protected in special courts, as some have recently proposed. An Ombudsman’s office should also be created to assist the Judicial Ombudsman with a staff of independent Ukrainian legal experts who are able to conduct legal research and investigations in time to help the Judicial Ombudsman provide appropriate opinions relatively quickly, as well as to act as deputy prosecutors to assist to implement and enforce opinions as necessary.

Benefits to Investors

For most investors, a full BIT arbitration process takes much too long to protect their investment, and also costs too much, usually many millions of US dollars. Typically, even where a denial of justice is eventually found in a BIT case, it is too late for the investor to recover its business or property, so the investor can only obtain a monetary award for damages against the state of Ukraine to compensate for the failure by Ukraine’s courts.

It can be difficult to collect on such awards in practice (despite Ukraine receiving much greater amounts in assistance from many of the foreign countries from which such investors come to Ukraine). By the time a BIT arbitration is completed, it is often also too late for the Ukrainian authorities to improve the judiciary by addressing the improper behaviour of the judges involved, who by then may have retired or even moved abroad.

Instead, the Judicial Ombudsman could review complaints about clearly wrongful court decisions in time to try to quickly save the litigant’s business and property before it is sold on or otherwise destroyed in value pursuant to the wrongful court decision. This intervention of the Ombudsman would allow the judges who were involved in such a wrongful decision to timely reconsider their decision, or otherwise result in new judges at the same court level reviewing the case in detail and the legal problems identified by the Ombudsman, in order to render a lawful decision.

The Judicial Ombudsman’s opinions should help safeguard the legal position of the investor or other litigant and secure its legal interests pending a rehearing. Investors would thereby have their businesses and property interests better protected from being quickly and wrongfully taken by third parties through clearly improper court action where the courts may act with little public attention, virtually in secret. The Ukrainian government could then also have a basis to intervene to compensate and otherwise assist an investor or other litigant that has been improperly attacked based on a clearly wrongful judicial decision.

To clarify, this proposed Judicial Ombudsman is to address clear abuses, and not to reconsider judicial decisions where there are reasonable arguments on both sides, and the judges have decided in favour of one party or the other in the reasonable exercise of their judgement, with such decisions being subject to ordinary appeal. However, losing in such cases is not a principal problem for investors in Ukraine. A legally well-advised investor in Ukraine should not end up with his business or assets being in jeopardy in close cases.

The problem currently in Ukraine is that even well-advised investors and others that have done everything properly are losing their property and rights due to judicial decisions that constitute clear denials of justice, for which BIT remedies are usually too slow or expensive to be of practical benefit. Instead, Ukraine needs something more effective to block what amounts to theft by gross judicial misbehaviour. The proposed Judicial Ombudsman is aimed at solving this problem.

Systematic Reform

Ukraine needs the systemic reform suggested above to address the lack of any effective independent outside oversight of the Ukrainian judiciary in order to quickly resolve the abuse problem from clearly wrongful court decisions that presumably result from corruption. This proposed reform focuses on what courts actually do, and responds to denials of justice for actual litigants in reality, rather than only in theory. The proposed Judicial Ombudsman should timely block such wrongful court decisions from effectively dispossessing investors and others of rights and property without any genuine legal justification, and thereby greatly benefit Ukraine by providing the foundation for the increase in investment that Ukraine and its citizens need.

This proposal for a Judicial Ombudsman could be relatively quickly and inexpensively implemented. It would prove much more effective than the total court reorganisation and replacement of judges that others are now calling for, which based on past experience, is unlikely to actually cure the existing problems.

As indicated, there are several stages for the possible implementation of the Judicial Ombudsman proposal. Currently, there is no independent reference point by which investors and other litigants can effectively complain to the Ukrainian government about denial of justice court decisions, even when it is clear to everyone that a travesty of justice has occurred that is depriving an investor or other litigant of its business and property. The creation of a Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman to review and render opinions on court decisions is urgently needed to provide this standard.

As the next stage, based on the Swedish prosecutorial model for its Justice Ombudsman, the Ukrainian Judicial Ombudsman could also be empowered to prosecute judges for their abuses, at least if the relevant wrongful judgements are not voluntarily rectified. This prosecutorial review process should quickly provide the Ukrainian judicial system with the systemic reform that it needs.

If even these measures do not do enough to combat entrenched corruption, then in a third stage, further powers should be given to the Judicial Ombudsman, so that the Ombudsman could intervene to quickly send cases back for review, before the victims of the described judicial misbehaviour can lose their property and rights.

Author: Bate C. Toms, Chairman of the British Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce and Managing Partner of the Law Offices of B. C. Toms & Co, Kyiv and London, JD Yale Law School.