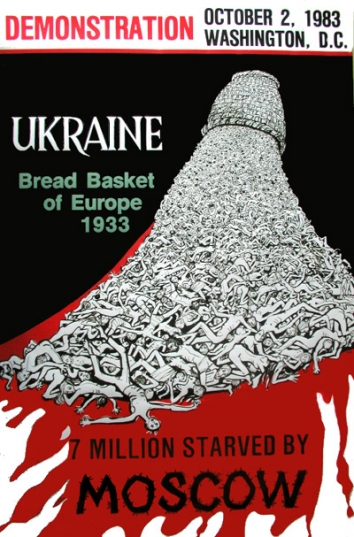

Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Ukraine’s Political “Frenemies” Seek To Avoid 2005-Style Split

.jpg) By Laurence Norman, The Wall Street Journal,

By Laurence Norman, The Wall Street Journal,

NY, NY, Tue, Nov 29, 2016

The two most important politicians in Ukraine are “frenemies,” one of them said in an interview in Brussels this week—a delicate love-hate relationship on which the future of the state depends.

Out of power for seven months, former Ukraine Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk has been made a kind of traveling ambassador-to-the West by the man who fired him, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko.

The election of Donald Trump and his promise to forge a new partnership with Russia has created deep uncertainty in Kiev about the future level of support the country can expect by the U.S.

And it is a dangerous time for Ukraine. Fighting continues in eastern Ukraine between Kiev and pro-Russian separatists. Politically, Yulia Tymoshenko, a former ally of Mr. Yatsenyuk, is trying to launch a comeback, leading protests against high energy bills and bank failures.

Mr. Yatsenyuk’s message to western leaders is to stay the course. He has visited U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Washington, German Chancellor in Angela Merkel in Berlin and was again in Brussels this week to see top European Union officials.

“My message to the global leaders is as follows. Look, we are still doing our jobs. Ukraine needs to be on your radars,” he said. “We do understand that you guys have a number of troubles… But please do not abandon us,” he said.

Mr. Yatsenyuk said Mr. Poroshenko would be wise to tread carefully with Mr. Trump, setting out Ukraine’s case against Russia’s interference in Ukraine and offering options for co-operation. He believes that ultimately, Mr. Trump will learn for himself the limits of working with Mr. Putin.

“Russia and the United States were, are and will be adversaries,” he said.

Mr. Yatsenyuk and Mr. Poroshenko are strong rivals, or in the former prime minister’s words “very, very strong frenemies.”

“Look, he is a smart guy,” Mr. Yatsenyuk said of Mr. Poroshenko. “Sometimes…he behaves like a tank — just moving forward. But you need always to have in your mind that there is an anti-tank missile out there,” he says.

The uneasy relations between Mr. Poroshenko and Mr. Yatsenyuk started the day after the president’s bloc failed to secure a parliamentary majority in 2014.

There were echoes, immediately with the demise of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine a decade before. A disastrous fracture in 2005 between then-President Victor Yushchenko and his former ally Ms. Tymoshenko heralded years of political acrimony which ended in the eclipse of the pro-western government in Ukraine. In 2010, Viktor Yanukovych, the pro-Russian candidate whom Mr. Yuschchenko had defeated in 2004, won the presidency.

Mr. Yatsenyuk said he was committed to avoidng a repeat of 2005. But for a time that is just what seemed to be happening.

Tensions spilled over in late 2015. Mr. Poroshenko and Mr. Yatsenyuk were losing popularity and facing growing pressure from western backers and domestic opponents to tackle corruption and re-energize the economy.

Mr. Poroshenko’s team was trying to push Mr. Yatsenyuk out, risking a split in the pro-western camp.

Mr. Yatsenyuk was attacked in parliament – lifted from the podium – by a lawmaker from the president’s bloc, triggering a parliamentary brawl. Days later, a fractious cabinet meeting ended with Ukraine’s interior minister throwing water into the face of the former Odessa governor, the former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili.

This time, things took a different turn than in 2005. Mr. Yatsenyuk quit in April but helped deliver the votes for a new government led by the president’s long-time aide Volodymyr Groysman. Avoiding snap elections, Mr. Yatsenyuk’s People’s Front bloc stayed in government, retaining six seats in Mr. Groysman’s cabinet.

Despite tensions and strains, Ukraine has since taken modest but politically difficult steps to rein in corruption and improve the economy.

Seven months after resigning, Mr. Yatsenyuk, who oversaw a government that prevented default amid a war and currency crisis but became deeply unpopular because of falling living standards and a perceived lack of progress in tackling corruption, notes the “huge political price” he paid for pushing unpopular measures. However the 42 year old, a close aide and top minister under Mr. Yushchenko in the 2000s, said his duty this spring was clear.

Mr. Yatsenyuk said his premiership under Mr. Poroshenko was an “extremely complicated and difficult co-habitation.” But he noted it lasted longer and was far more productive than the first Yushchenko-Tymoshenko collaboration. That experience, he said, “entirely undermined Ukraine’s reputation.”

“I could not dare to let it happen once again,” he said.

“My biggest concern was not to make a replica of relations between Tymoshenko and Yushchenko,” he said. “Because, you know there was no winner after this. The only winner was Mr. Yanukovych and…Russians.”