Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

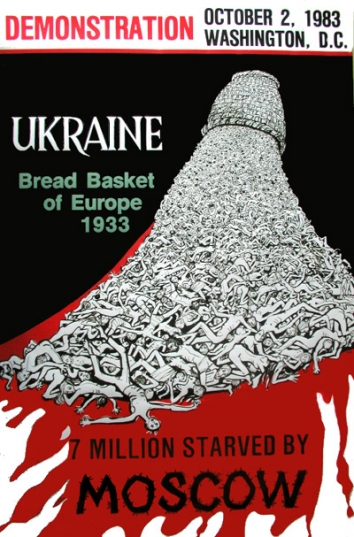

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

THE UKRAINE LIST (UKL) #490

Compiled by Dominique Arel

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, University of Ottawa

Ottawa, Canada, May 24, 2018

Compiled by Dominique Arel

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, University of Ottawa

Ottawa, Canada, May 24, 2018

Compiled by Dominique Arel

Compiled by Dominique Arelcompiled by Dominique Arel (darel@uottawa.ca)

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, U of Ottawa

24 May 2018

**For regular postings on Ukraine and Ukrainian Studies, follow me on Twitter at @darelasn **

1-Danyliw Seminar 2018 Call for Proposals (21 June 2018 Deadline)

2-ASN 2018 Post-Convention Announcement

3-Kule Doctoral Scholarships on Ukraine, uOttawa (1 February 2019 Deadline)

4-New Book: Marci Shore, The Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution

5-New Book: Anna Matveeva, Conflict in Southeastern Ukraine Explained from Within

6-New Book: Haran & Yakovlyev, eds., Constructing a Political Nation [free PDF]

7-New Book: Taras Kuzio, Putin’s War Against Ukraine

8-Guardian: MH17 Downed by Russian Military Missile System, Investigators Say

9-Kyiv Post: Ukrainian Government Accused of Fooling West on Anti-Graft Court

**Oleg Sentsov, Four Years of Imprisonment in Russia**

10-Hromadske: How Russia is Tormenting Sentsov and Kolchenko [Video + Text]

11-Nationalities Papers: Dominique Arel, Review of The Trial

12-Danyliw Seminar: Transcript of the Q&A with The Trial’s filmmaker Askold Kurov

13-PONARS: Volodymyr Ishchenko, The Extra-Parliamentary Power of the Far Right

14-ZoiS Spotlight: Gwendolyn Sasse, Linking Language and Security in Ukraine

15-American Interest: Peter Pomerantsev, The Seven Ages of Revolution (11 January)

**Kennan Institute (KI) and Its Kyiv Office: Three Open Letters**

16-Kennan Ukraine Alumni: On the KI’s Growing Pro-Kremlin Policies (27 February)

17-Letter of Scholars in Support of Professor Mikhail Minakov (5 March)

18-Ukrainian Scholars on the Closure of Kennan Institute Kyiv Office (15 April)

19-RFE/RL: Sergei Loznitsa Wins Best Director in Cannes Festival Sidebar

20-Variety: Review of “Donbass,” by Loznitsa (Un Certain Regard Sidebar)

21-CIUS 40th Anniversary Conference Proceedings Online

22-AAUS Prizes to Lynne Viola (Book) and Heather Coleman (Article)

23-AAUS Board Members and Officers

#1

14th Annual Danyliw Research Seminar on Contemporary Ukraine

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, University of Ottawa, 8-10 November 2018

CALL FOR PAPER PROPOSALS

Deadline: 21 June 2018

The Chair of Ukrainian Studies, with the support of the Wolodymyr George Danyliw Foundation, will be holding its 14th Annual Danyliw Research Seminar on Contemporary Ukraine at the University of Ottawa on 8-10 November 2018. Since 2005, the Danyliw Seminar has provided an annual platform for the presentation of some of the most influential academic research on Ukraine.

The Seminar invites proposals from scholars and doctoral students —in political science, anthropology, sociology, history, law, economics and related disciplines in the social sciences and humanities— on a broad variety of topics falling under thematic clusters, such as those suggested below:

Conflict

•war/violence (combatants, civilians in wartime, DNR/LNR, Maidan)

•security (conflict resolution, Minsk Accords, OSCE, NATO, Crimea)

•nationalism (Ukrainian, Russian, Soviet, historical, far right)

Reform

•economic change (energy, corruption, oligarchies, EU free trade, foreign aid)

•governance (rule of law, elections, regionalism, decentralization)

•media (TV/digital, social media, information warfare, fake news)

Identity

•history/memory (World War II, Holodomor, Soviet period, interwar, imperial)

•language, ethnicity, nation (policies and practices)

•culture and politics (cinema, literature, music, performing arts, popular culture)

Society

•migration (IDPs, refugees, migrant workers, diasporas)

•social problems (reintegration of combatants, protests, welfare, gender, education)

•state/society (citizenship, civil society, collective action/protests, human rights)

**To mark the 85th Anniversary of the Ukrainian Famine (Holodomor), a number of papers/events will be devoted to the Holodomor. Holodomor-related proposals are most welcome**

The Seminar will also be featuring panels devoted to recent/new books touching on Ukraine, as well as the screening of new documentaries followed by a discussion with filmmakers. In 2017, new books by Oleh Havrylyshyn, Yuliya Yurchenko and Mayhill Fowler were featured, as well as the films The Trial (by Askold Kurov) and Alisa in Warland (by Alisa Kovalenko), with the filmmakers present. Information on the 2016 and 2017 book panels and films can easily be accessed from the top menu of the web site. The 2018 Seminar is welcoming book panel proposals, as well as documentary proposals.

Presentations at the Seminar will be based on research papers (6,000-8,000 words) and will be made available, within hours after the panel discussions, in written and video format on the Seminar website and on social media. The Seminar favors intensive discussion, with relatively short presentations (12 minutes), comments by the moderator and an extensive Q&A with Seminar participants and the larger public.

People interested in presenting at the 2018 Danyliw Seminar are invited to submit a 500 word paper proposal and a 150 word biographical statement, by email attachment, to Dominique Arel, Chair of Ukrainian Studies, atdarel@uottawa.ca AND chairukr@gmail.com. Please also include your full coordinates (institutional affiliation, preferred postal address, email, phone, and Twitter account [if you have one]). If applicable, indicate your latest publication or, in the case of doctoral or post-doctoral applicants, the year when you entered a doctoral program, the title of your dissertation and year of (expected) completion. Note that a biographical is not a CV, but a written paragraph.

Books published between 2017 and 2019 (as long as near-final proofs are available prior to the Seminar) are eligible for consideration as a book panel proposal. The proposal must include a 500 word abstract of the book, as well as the 150 word bio and full coordinates.

Films produced between 2016 and 2018 are eligible for consideration as a documentary proposal. The proposal must include a 500 word abstract of the film, as well as the 150 word bio, full coordinates, and a secure web link to the film.

In addition to scholars and doctoral students, policy analysts, practitioners from non-governmental and international organizations, journalists, and artists are also welcome to send a proposal.

The proposal deadline is 21 June 2018. The Chair will cover the travel and accommodation expenses of applicants whose proposal is accepted by the Seminar. The proposals will be reviewed by an international selection committee and applicants will be notified in the course of the summer.

To celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the Danyliw Seminar in 2014, a special website was created at www.danyliwseminar.com. The site contains the programs, papers, videos of presentations and photographs of the last fourseminars (2014-2017). To access the abstracts, papers and videos of the 2017 presenters, click on “Participants” in the menu and then click on the individual names of participants. The 2017 Program can be accessed athttps://www.danyliwseminar.com/program-2017.

Check the “Danyliw Seminar” Facebook page at http://bit.ly/2rssSHk.

For information on the Chair of Ukrainian Studies, go to https://www.chairukr.com. (The site is being re-developed).

The Seminar is made possible by the generous commitment of the Wolodymyr George Danyliw Foundation to the pursuit of excellence in the study of contemporary Ukraine.

#2

ASN 2018 Post-Convention Announcement

The Association for the Study of Nationalities (ASN) held its 23rd Annual World Convention on 3-5 May 2018 at the Harriman Institute, Columbia University, New York. The Convention Awards were announced at a special ceremony on Saturday May 5.

The ASN Doctoral Student Awards, to honor the best graduate papers, were given to

•Albana Shehaj (U of Michigan, US, Political Science) on the puzzle of the electoral durability of corrupt politicians despite popular protests against graft; and Iva Vukusic (Utrecht U, Netherlands, History) on the evidence of Balkans war paramilitary violence in war crimes trials – both in the Balkans Section;

•Andrea Peinhopf (U College London, UK, Political Science/Sociology) on how the mass population displacement in the 1992 Abkhazia War affected those who were left behind (Russia/Caucasus Section);

•Susan Divald (U of Oxford, UK, Political Science/International Relations) on the variation in the Hungarian claims to autonomy in Slovakia (Central Europe Section)

•Karolina Kluczewska (U of St. Andrews, UK, International Relations) on how the notion of “good governance” promoted by American donors is carried out by local NGOs in Tajikistan (Eurasia/Turkey Section);

•Natalia Stepaniuk (U of Ottawa, Canada, Political Science) on the civilian volunteers who provide assistance to refugees and combatants in Donbas (Ukraine Section);

•Livia Rohrbach (U of Copenhagen, Denmark, Political Science) on the divergent outcomes of the bargaining process over self-determination (Nationalism/Migration Section)

The Harriman ASN Rothschild Book Prize went to Evgeny Finkel for Ordinary Jews: Choice and Survival during the Holocaust (Princeton University Press, 2017), which explains the variation in Jewish survival strategies (collaboration, rebellion, escape) in three ghettos during the Holocaust (Minsk, Kraków and Białystok). Honorable mentions were given to Kelly O’Neill for Claiming Crimea: A History of Catherine the Great’s Southern Empire (Yale, 2017), and to Mikhail A. Alexseev and Sufian N. Zhemukhov for Mass Religious Ritual and Intergroup Tolerance: The Muslim Pilgrims’ Paradox (Cambridge, 2017).

The ASN Huttenbach Prize for Best Article in Nationalities Papers was given to Dana Landau for “The Quest for Legitimacy in Independent Kosovo: The Unfulfilled Promise of Diversity and Minority Rights,” which appeared in the Vol. 45. No. 3 issue of the journal. Henry Huttenbach, a founding member of ASN, was a long time Editor of Nationalities Papers.

The ASN Documentary Award went to The Red Soul (Netherlands, 2017), from director Jessica Gorter, on the ambivalent memory of Stalin in contemporary Russia, https://www.asnconvention.com/the-red-soul. Honorable mentions were given to The Other Side of Everything (Serbia/France/Qatar, 2017), directed by Mila Turajlic, on the unresolved legacy of civil war in Serbia, https://www.asnconvention.com/the-other-side-of-everything, and to Intent to Destroy (US, 2017), directed by Joe Berlinger, on the Armenian genocide and its denial, https://www.asnconvention.com/intent-to-destroy.

The ten most attended panels/events at the Convention were

--A Conversation with Timothy Snyder on The Road to Unfreedom

--the roundtable on David Laitin’s Identity in Formation Twenty Years Later

--the roundtable “Russian Under Putin—After the Presidential Election”

--the film The Red Soul

--the Symposium on “Identities in Flux in post-Maidan Ukraine”

--A Conversation with Serhii Plokhy on Chernobyl: History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

--the panel “Inclusion and Exclusion in the Western Balkans”

--the roundtable “Polish Memory Law: When History Becomes a Source of Mistrust”

--the panel “The Far Right in Europe and North America”

--the roundtable “Reflection on Peaceful Protest and Tranformation in Armenia”

The Conventiom hosted panelists traveling from 42 different countries and featured 152 panels/events, including 25 book panels and 14 new documentaries.

ASN wishes to express its gratitude to the Harriman Institute for its exceptional support in making the event a remarkable success. Special acknowledgments are reserved for ASN Executive Director Ryan Kreider, Convention Manager Ilke Denizli, Convention Registration Manager Kelsey Davis, Convention Communications Manager Agathe Manikowski and University of Ottawa Student Coordinator Catherine Corriveau, with warm kudos to the Harriman/SIPA student staff and from the University of Ottawa student team.

The next ASN Convention will take place on 2-4 May, 2019, at the Harriman Institute, Columbia University. The Call for Papers will be issued in early September and the submission deadline will fall on October 25, 2018.

An ASN European Conference, “Nationalism in Times of Uncertainty,” will take place at the University of Graz, Austria, on 4-6 July 2018.

For more information on the ASN World Convention: https://www.asnconvention.com

For more information on ASN, http://www.nationalities.org.

#3

Kule Doctoral Scholarships on Ukraine

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, University of Ottawa

Application Deadline: 1 February 2019 (International & Canadian Students)

https://www.chairukr.com/kule-doctoral-scholarships

The Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Ottawa, the only research unit outside of Ukraine predominantly devoted to the study of contemporary Ukraine, is announcing a new competition of the Drs. Peter and Doris Kule Doctoral Scholarships on Contemporary Ukraine. The Scholarships will consist of an annual award of $22,000, with all tuition waived, for four years (with the possibility of adding a fifth year).

The Scholarships were made possible by a generous donation of $500,000 by the Kule family, matched by the University of Ottawa. Drs. Peter and Doris Kule, from Edmonton, have endowed several chairs and research centres in Canada, and their exceptional contributions to education, predominantly in Ukrainian Studies, has recently been celebrated in the book Champions of Philanthrophy: Peter and Doris Kule and their Endowments.

Students with a primary interest in contemporary Ukraine applying to, or enrolled in, a doctoral program at the University of Ottawa in political science, sociology and anthropology, or in fields related with the research interests of the Chair of Ukrainian Studies, can apply for a Scholarship. The competition is open to international and Canadian students.

The application for the Kule Scholarship must include a 1000 word research proposal, two letters of recommendation (sent separately by the referees), and a CV and be mailed to Dominique Arel, School of Political Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences Building, Room, 7067, University of Ottawa, 120 University St., Ottawa ON K1N 6N5, Canada.

Applications will be considered only after the applicant has completed an application to the relevant doctoral program at the University of Ottawa. Consideration of applications will begin on 1 February 2019 and will continue until the award is announced.

The University of Ottawa is a bilingual university and applicants must have a certain oral and reading command of French. Specific requirements vary across departments.

Students interested in applying for the Scholarships beginning in the academic year 2017-2018 are invited to contact Dominique Arel (darel@uottawa.ca), Chairholder, Chair of Ukrainian Studies, and visit our web sitewww.chairukr.com.

#4

New Book

Marci Shore

The Ukrainian Night

An Intimate History of Revolution

Yale University Press, 2018

What is worth dying for? While the world watched the uprising on the Maidan as an episode in geopolitics, those in Ukraine during the extraordinary winter of 2013–14 lived the revolution as an existential transformation: the blurring of night and day, the loss of a sense of time, the sudden disappearance of fear, the imperative to make choices. In this lyrical and intimate book, Marci Shore evokes the human face of the Ukrainian Revolution. Grounded in the true stories of activists and soldiers, parents and children, Shore’s book blends a narrative of suspenseful choices with a historian’s reflections on what revolution is and what it means. She gently sets her portraits of individual revolutionaries against the past as they understand it—and the future as they hope to make it. In so doing, she provides a lesson about human solidarity in a world, our world, where the boundary between reality and fiction is ever more effaced.

Marci Shore is associate professor of history at Yale University and award-winning author of Caviar and Ashes and The Taste of Ashes. She has spent much of her adult life in Central and Eastern Europe.

#5

New Book

Anna Matveeva

Through Times of Trouble

Conflict in Southeastern Ukraine Explained from Within

Lexington Books, 2018

This book tells the story of insurgency in Ukraine’s Donbas region from the perspective of the rebels, who sought and continue to seek either independence from Ukraine or unification with Russia. As such, it provides a unique insight into their thinking and motivations, which need to be understood if the conflict is to be resolved. Those making and remaking the conflict are placed in the centre of the story which uses the words of the combatants themselves. It shows how volunteer fighters, driven by a wide and diffuse set of motivations, emerged from Ukraine, Russia, and different parts of the world, stood at the rebellion's heart. The book focuses on the participants’ own voices and personalities, drawing extensively on first-hand research and interviews.

Rather than rendering Ukraine a chess piece on the geopolitical board, the rebellion shows that ordinary people, rather than elites, can act as a decisive force. Donbas says something about why large numbers of people make the decision to take part in a collective violent action, when material rewards are low or non-existent, and mortal risks high. It stands as an important text on the study of modern insurgencies, revealing how violent conflicts happen via issues of politicized identity and involvement of non-state actors. This book places this conflict into the context of other conflicts worldwide and demonstrates how ideas and narratives are constructed to provide meaning to a struggle. The insurgency has produced a conflict sub-culture, rich with symbolism, narrative, and communications, made possible by the digital age and a social media-savvy population. These beliefs and ideas have had the power to pull people from different parts of the world.

#6

New Book

Olexiy Haran and Maksym Yakovlyev, eds.

Constructing a Political Nation

Changes in the Attitudes of Ukrainians during the War in the Donbas.

Stylos Publishing, 2018

https://bit.ly/2ILuDEr [PDF downloadable]

What effect did Russia’s attack have on Ukrainian society and on public opinion? And how, in turn, did they influence Ukrainian identity and politics? This book, prepared by the School for Policy Analysis, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy with the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, shows that contrary to the Kremlin’s expectations, Russian aggression has in fact led to a strengthening of the Ukrainian political nation. The book covers national and regional dimensions of changes in the attitudes of Ukrainians during the war in the Donbas: identity issues, political and party preferences, approaches to decentralization and the conflict in the Donbas, economic tendencies, changes in foreign policy attitudes toward the EU, NATO, and Russia. In the afterword to this book, possible scenarios for Ukraine’s future policy toward the occupied territories have been presented.

The first edition appeared in March 2017 in Ukrainian. This is now the second, updated edition and the first in the English language. The project was supported by the State Fund for Fundamental Research of Ukraine, the Kennan Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the International Renaissance Foundation, the Fulbright Program in Ukraine, administered by the Institute of International Education, and the Ukrainian Fulbright Circle.

Iryna Bekeshkina, Decisive 2014: Did It Divide or Unite Ukraine?

Iryna Bekeshkina and Oleksii Sydorchuk, The Party System after the Maidan: Regional Dimensions of an Unfinished Transformation

Ihor Burakovskiy, Russian Aggression in the Donbas as a Factor in the

Formation of Economic Sentiments in Ukraine

Maria Zolkina and Oleksiy Haran, Changes in the Foreign Policy Orientations of Ukrainians after the Euromaidan: National and Regional Levels

Maria Zolkina, The Donbas: New Trends in Public Opinion

Ruslan Kermach, Attitudes of Ukrainians toward Russia and Russians: Dynamics and Main Trends

#7

New Book

Taras Kuzio

Putin’s War Against Ukraine

Revolution, Nationalism, and Crime

Published in association with the Chair of Ukrainian Studies

University of Toronto

The West has woken up to the uncomfortable fact that Russia has long believed it is at war with them, the most egregious example of which is Vladimir Putin’s hacking of the US elections. For Western governments, used to believing in the post-Cold War peace dividend, it came as a shock to find the liberal international order is under threat from an aggressive Russia. The ‘End of History – loudly proclaimed in 1991 – has been replaced by the ‘Return of History.’ Putin’s War Against Ukraine came three years earlier when he launched an unprovoked war in the Donbas and annexed the Crimea. Putin’s war against Ukraine has killed over 30, 000 civilians, Ukrainian and Russian soldiers and Russian proxies, forced a third of the population of the Donbas to flee, illegally nationalised Ukrainian state and private entities in the Crimea and the Donbas, destroyed huge areas of the infrastructure and economy of the Donbas, and created a black hole of crime and soft security threats to Europe. Putin's War Against Ukraine is the first book to focus on national identity as the root of the crisis through Russia's long-term refusal to view Ukrainians as a separate people and an unwillingness to recognise the sovereignty and borders of independent Ukraine.

Written by Taras Kuzio, a leading authority on contemporary Ukraine, the book is a product of extensive fieldwork in Russian speaking eastern and southern Ukraine and the front lines of the Donbas combat zone. Putin’s War Against Ukraine debunks myths surrounding the conflict and provides an incisive analysis for scholars, policy makers, and journalists as to why Vladimir Putin is at war with the West and Ukraine.

#8

MH17 Downed by Russian Military Missile System, Say Investigators

by Shaun Walker

Guardian, 24 May 2018

An international team of investigators say they have uncovered hard evidence that a Russian military missile system fired the missile that shot down flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine in 2014.

The Malaysia Airlines Boeing 777 was travelling from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur when it was shot down over the conflict zone in eastern Ukraine on 17 July 2014. All 298 people onboard were killed.

In 2016, investigators announced they had evidence that the BUK systeminvolved in the incident had crossed the border into eastern Ukraine from Russia and returned after the plane had been shot down.

The joint investigation team (JIT) looking into the incident is made up of Dutch prosecutors and police and others from Australia, Malaysia and Ukraine.

At a press conference in The Hague on Thursday, the investigators showed photo and video evidence that they said proved they had identified the specific BUK system responsible for shooting down the plane. They said they had “legal and convincing evidence which will stand in a courtroom” that the BUK system involved came from the 53rd anti-aircraft missile brigade based in Kursk, in western Russia.

For the first time, the investigators appeared to confirm that the Russian military was complicit in the downing of the plane, at the very least by providing the missile system used. Previously, the investigative website Bellingcat has pointed to involvement of the same brigade using open-source information.

Russian officials have denied all involvement in the incident, and Kremlin-linked media outlets have floated a range of implausible theories suggesting Ukraine was responsible for shooting down the plane. Russia has used its veto in the UN to prevent an international tribunal from being set up to determine guilt, meaning any eventual trial would be held in the Netherlands under Dutch law.

Fred Westerbeke, the chief prosecutor, said the investigation was in its last phase but could not say when he would be ready to file indictments. Two years ago, prosecutors said there were about 100 people under suspicion of direct or indirect involvement. On Thursday, Westerbeke said that number had come down to several dozen, but he declined to name them.

He said there was other evidence that would be kept secret until a court hearing began. “We don’t want to tell everything we know because then we are opening our cards to the other side and we do not want to do that.”

Investigators had asked Russian authorities for information about the 53rd brigade but had been ignored, said Westerbeke.

In a sign that some evidence is still missing, the JIT repeated a call for those with information about the incident to come forward, including information about the 53rd brigade, promising anonymity. No information was given as to whether investigators believed the BUK system was deployed as part of a Russian military mission.

Bellingcat said it would hold a press conference on Friday to present new findings on MH17.

Russia has repeatedly denied it was militarily active in eastern Ukraine, despite an overwhelming body of evidence to the contrary. In 2014, Russian troops and hardware were introduced at key moments to back pro-Russia separatists fighting against Ukrainian government troops.

In the weeks before MH17 was shot down, the separatists had shot down a number of Ukrainian military planes over east Ukraine.

This week a group of families of the MH17 victims wrote an open letter to the Russian people before the World Cup begins in Russia next month.

“We are painfully aware of the dark irony that the Russian leaders who will profess to welcome the world with open arms are those who are chiefly to blame for shattering our world,” the letter says. “And that it is these same leaders who have persistently sought to hide the truth, and who have evaded responsibility ever since that dreadful day in July 2014.”

#9

Ukrainian Government Accused of Fooling West on Anti-Graft Court

by Oleg Sukhov

Kyiv Post, 24 May 2018

Ukrainian authorities and the nation’s foreign donors have entered the final stage of talks on creating an anti-corruption court.

The Verkhovna Rada on May 23 and May 24 considered hundreds of amendments to a bill to create an anti-corruption court but did not have enough time to pass the bill itself in the second reading as of 4 p.m. on May 24. It was adopted in the first reading on March 1.

However, the negotiations between Ukraine and its foreign partners on the anti-corruption court have been heavily lambasted by members of the Public Integrity Council, the judiciary’s civil society watchdog. They believe foreign donors have been deceived by Ukrainian authorities, which will now get Western money but will still be able to rig the competition for anti-corruption judges.

Ukrainian authorities deny the accusations.

The creation of the anti-corruption court is a necessary precondition for another $2 billion tranche of the International Monetary Fund.

The conditions pushed for by Western partners will still enable President Petro Poroshenko to create a puppet court without a proper transparent competition and stack it with his cronies, Public Integrity Council members say.

“Effectively, international donors will be completely isolated from the selection of the best candidates for the anti-corruption cour, ” Roman Kuybida, a member of the council, said in an op-ed for the Kyiv Post. “The Public Council of International Experts can be used as a façade to cover up for the results of a competition influenced by political and oligarchic elites through members of the High Qualification Commission.”

“It is crucial that the Expert Panel—consisting of independent people with extensive and recognized expertise in the area of fighting corruption—is given a crucial role in verifying that applicants to the position of a judge on the High Anti-Corruption Court have the necessary qualifications related to corruption adjudication,” Mr. Goesta Ljungman, the International Monetary Fund’s resident representative in Ukraine, told the Kyiv Post. “The recommendation issued by the Expert Panel should be respected, and candidates who do not meet the criteria for anti-corruption judges should be disqualified from further consideration in the selection process.”

Ljungman said that the discussions on the bill were “ongoing.”

Satu Kahkonen, World Bank Country Director for Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine, told the Kyiv Post that “for the court to be effective, its independence needs to be ensured.”

Flawed compromise

According to the ongoing negotiations, the seven-member Council of International Experts, which will be delegated by Ukraine’s foreign partners and donors, will be able to veto candidates for the anti-corruption court nominated by the 16-member High Qualification Commission.

A joint session of the Council of International Experts and the High Qualification Commission will be able to override such vetoes.

Allies of Poroshenko insist that at least 16 votes should be enough to override vetoes by the Council of International Experts on candidates. This means that the High Qualification Commission’s 16 votes will be enough, and foreign donors’ opinion can be ignored.

Ukraine’s foreign partners say that at least 20 votes should be necessary to override a veto by foreign partners.

But Public Integrity Council members Kuybida and Vitaly Tytych believe that foreign powers’ veto powers will be useless because they will not have any oversight over the actual selection of judges. As a result, the commission will choose the worst and most politically loyal candidates, and it will not matter whether any of them will be vetoed, Tytych and Kuybida argue.

Moreover, good and independent candidates will not even run in the competition because they know they will be blocked by the commission, Tytych said.

Powerless foreigners

The Public Integrity Council believes that foreign partners must be allowed not only to veto the worst candidates but also choose the best candidates.

To make the competition fair and objective, the competition for the anti-corruption court must be held by a special chamber of the High Qualification Commission comprising a majority of foreign representatives, Tytych and Kuybida argued.

The Venice Commission’s recommendations (clause 73 of Conclusion No. 896/2017) stipulate that foreign partners must be included in the competition commission or even the High Qualification Commission’s composition.

The Public Integrity Council’s role, which should be able to veto candidates based on integrity criteria, must also be preserved during the competition for anti-corruption judges, Kuybida said.

Flawed methodology

Another way to hold a fair competition is to make the assessment methodology objective and deprive the High Qualification of its arbitrary powers to assess candidates, Tytych argued.

During the Supreme Court competition, 90 points were assigned for anonymous legal knowledge tests, 120 points for anonymous practical tests, and the High Qualification Commission could arbitrarily assign 790 points out of 1,000 points without giving any explicit reasons.

To make the competition’s criteria objective, the law on the judiciary must be amended to clearly assign 750 points for anonymous legal knowledge tests and practical tests (for competitions for both the anti-corruption court and all other courts), Tytych argued.

Moreover, the authorities may sabotage corruption cases through the discredited Supreme Court, which will be the cassation court for graft trials.

A special autonomous anti-corruption chamber of the Supreme Court should be selected under the same procedure as the High Anti-Corruption Court, Kuybida said.

Other aspects

One of the only concessions that Ukrainian authorities made to Western partners is that they agreed to make the conditions for becoming an anti-corruption judge less strict. In Poroshenko’s original bill, they were so strict that it would be almost impossible to find candidates meeting the demands, and the selection could drag on for years.

Ukrainian authorities also agreed to amend the bill to make sure that the court considers all cases of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine and does not consider non-NABU cases.

Discredited commission

Public Integrity Council members argued that the competition for the anti-corruption court should not be entrusted to the discredited High Qualification Commission because they believe it rigged the Supreme Court competition and brought it under Poroshenko’s control. The commission denies the accusations.

First, during the practical test stage, some candidates were given tests that coincided with cases that they had considered during their career, which was deemed a tool of promoting political loyalists.

Second, in the High Qualification Commission illegally allowed 43 candidates who had not gotten sufficient scores during practical tests to take part in the next stage, changing its rules amid the competition. Members of the Public Integrity Council believe that the rules were unlawfully changed to prevent political loyalists from dropping out of the competition.

Third, the High Qualification Commission and the High Council of Justice illegally refused to give specific reasons for assigning specific total scores to candidates and refused to explain why the High Qualification Commission has overridden vetoes by the Public Integrity Council on candidates who do not meet ethical integrity standards.

Moreover, the commission nominated thirty discredited judges who do not meet integrity standards (according to the Public Integrity Council) for the Supreme Court, and Poroshenko has already appointed 27 of them (out of 115 appointees). These judges have undeclared wealth, participated in political cases, made unlawful rulings (including those recognized as unlawful by the European Court of Human Rights) or are investigated in corruption cases.

#10

From Crimea to Siberia:

How Russia is Tormenting Political Prisoners Sentsov and Kolchenko

Hromadske International, 17 May 2018

[With a 64-minute video]

Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov and activist Sasha Kolchenko were both detained in occupied Crimea on May 10, 2014. They were accused of plotting terrorist acts, taken to Russia and convicted. Kolchenko was sentenced to 10 years in prison and Sentsov – 20 on fabricated charges and based on testimonies given under tortures.

Two other Ukrainians – Gennadiy Afanasiev and Oleksiy Chirniy – were arrested with Sentsov and Kolchenko. Afanasiev was released in a 2016 prisoner exchange, and Chirniy is still in a penal colony in Magadan.

Four years after his arrest and thousands of kilometers away from his initial place of detention, Sentsov announces a hunger strike. His sole condition for its end is the release of all Ukrainian political prisoners located on the territory of the Russian Federation. Together with the ones that are held in Russia-occupied Crimea, there are 64 of them.

Of the 64 political prisoners, 27 are held on the territory of the Russian Federation while the rest are in Crimea. Among them, 58 were detained on the territory of the occupied peninsula.

Sentsov and Kolchenko were first held in a detention center in Moscow, tried in Rostov, transported to the Urals and then to the Russian Arctic. Between the two of them, they have covered almost 20,000 kilometers, or, half the distance around the Earth. Their entire journey has been within Russia. Or actually, within its prison system.

We travelled to the key sites along their transport route – where the Ukrainian consuls were denied access and where lawyers today face difficulties getting in – to find out in what conditions they are being kept and who is responsible for their fate.

#11

The Trial: The State of Russia vs. Oleg Sentsov. Directed by Askold Kurov. Produced by Marx Film (Estonia), Message Film (Poland) and Czech Television, with the support of the Polish Film Institute, the B2B Doc network and the Ukrainian Association of Cinematographers. 2017, 70 minutes. Contact: Anja Dziersk, Rise & Shine (Berlin), anja.dziersk@riseandshine-berlin.de. Webpage: https://www.asnconvention.com/the-trial. Shown at the ASN 2017 World Convention.

Dominique Arel

Chair of Ukrainian Studies, University of Ottawa

Forthcoming in Nationalities Papers

In 2011, Oleg Sentsov, a Crimean filmmaker, made waves on the international festival circuit with Gaamer, a documentary on computer gaming. During the Maïdan protests, he went to Kyïv to join “Avtomaïdan,” a group of activists who used their cars to picket the houses of government officials. During the Russian military occupation in Crimea, he organized humanitarian missions for Ukrainian soldiers trapped in their compounds, bringing them food and medication and assisting in the evacuation of their families. Outside of the strong Crimean Tatar national movement, Sentsov was arguably the most famous Maïdan activist in Crimea.

In May 2014, Sentsov was arrested on charges of “terrorism,” along with three alleged co-conspirators — Oleksiy Chornyi, Hennadiy Afanasyev and Oleh Kolchenko. Russian TV, citing sources from the FSB, Russia’s internal security police, announced that the suspects were linked to Pravyi sektor, a far-right Ukrainian movement involved in violent resistance on Maidan, and planned to blow up bridges and railway tracks in Crimea’s three major cities — Simferopol, Sevastopol and Yalta. It was later claimed that Sentsov was the main organizer.

The Trial, by Russian filmmaker Askold Kurov — known for documentaries on gay oppression in Russia (Children 404) and the Lenin Museum in Moscow (Leninland) -- follows the legal proceedings in Russia: first in a Lefortovo district courtroom in Moscow, for two hearings that extended his pre-trial detention; and then in Rostov, in Southern Russia, for the trial itself. The courtroom scenes allow us to see how a political trial with a predetermined outcome actually functions in Russia. The cruelty of the state gives pause, but its actors come out small. The prosecutor and judges merely go through the motions, reading without conviction legalese-laden testimonies and verdicts, while pretending that the law is being observed. (The multiple mentions that Sentsov and the witnesses who implicated him were tortured is never acknowledged). Sentsov tells the judge not to take it personally that “the court of an occupier cannot be just,” but he has no respect for the truly powerful —the FSB (“the Federal Service of Banditry”), and Putin (a “bloodthirsty dwarf”). He knows no fear. In his last words, he cites Bulgakov, that the greatest sin on earth is cowardice: “Everyone in the courtroom understand perfectly well that there are no fascists in Ukraine and that Crimea was annexed illegally.” One-third of the Russian population do not believe Russian propaganda, but they are afraid to act.

One Russian citizen who is not afraid is Alexander Sokurov, one of Russia’s most celebrated film directors. In a chilling scene, at an official televised function with nearly 100 people seated around a table, Sokurov confronts Putin over Sentsov, “begging” him to solve the problem: “A film director should be battling me at film festivals,” not sitting in jail. Putin responds that Sentsov was not convicted for his work, but because he has “de facto dedicated his life to terrorist activities.” Twice, Sokurov pushes back, invoking the “Russian and Christian way to hold mercy over justice.” Putin icily replies that “we cannot act (...) without a court judgment.” Everyone knows that the court judgment will be a political order but only Sokurov has the courage to stand up.

The film, in interviews with lawyers and court testimonies, leaves no doubt that the case is a complete fabrication, based on a modicum of actual or intended low-grade violence, unrelated to Sentsov. In early April 2014, Chornyi, Afanasyev and Kolchenko commit arson, in the middle of the night, against the empty offices of local pro-Russian organizations which supported the annexation. The damages are so light that a policeman shouts that it is not necessary to call the firemen. Afterwards, Chornyi makes plans on his own to blow up a Lenin statue and seeks advice from a chemistry student named Pirogov. Pirogov becomes an FSB informer and films a later encounter with Chornyi discussing his plans.

Chornyi was arrested before he can act and Afanasyev was also picked up. They were tortured to implicate Sentsov, whom they had never met. They both cracked (in the case of Afanasyev, the torture involved choking on his own vomit and having his testicles electrocuted). Sentsov was also tortured, threatened that if he did not admit his participation in the “conspiracy,” he would be made his ringleader and sentenced to 20 years, which is exactly what eventually happens. An initial search finds nothing but Soviet anti-fascist films, presented by a clueless FSB as evidence of his membership in Pravyi sektor. A subsequent search comes up with a planted gun.

The question is why frame Sentsov? The Russian political scientist Kirill Rogov, who appears twice in the film, invokes the “Khodorkovky principle,” named after the Russian oligarch who was sent to jail on alleged corruption charges: being famous will not protect you from the arbitrariness of the state, and therefore anyone is fair game. Sentsov’s lawyers claim that the FSB needed someone famous to symbolize the Pravyi sektor threat in Crimea. The film does not elaborate on what appears to be the key motive — Russia’s attempt to legitimize the annexation of Crimea.

Besides the fear that NATO might dislodge the Black Sea Fleet, the immediate claim by Russia was that the Crimean population, in majority ethnic Russian, was under physical threat from a “coup d’état” by “fascists” in Kyiv. Since actual threats could not be found, they had to be invented. Hours before the Russian Duma authorized Putin to send troops in Ukraine, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that the local Crimean Ministry of Interior had been attacked by “unknown men,” failing to clarify that the attackers were pro-Russian militias, working in concert with Russian troops already occupying parliament and communication hubs. Weeks later, the only incidents were isolated cases of vandalism. The Sentsov case symbolizes the lie that Russia came to the rescue of Crimean civilians against Maidan activists willing to engage in “terrorism.” At latest count, 23 Crimeans have been arrested or convicted of terrorism, always for alleged conspiracies.

This vital film, made with the involvement of film institutions from five East European countries, is also revealing on the meaning of Ukrainian national identity. In an interview on Crimean television prior to Maidan, Sentsov, an ethnic Russian, is asked if he considers himself a Ukrainian filmmaker. He simply answers “Yes, I am a citizen of Ukraine.” At the trial, when Kolchenko has to formally identify his nationality, he replies “Russian, Ukrainian,” as if to suggest that his identification with Ukraine is self-evident. A stunning scene is when Afanasyev, brought in to incriminate Sentsov, recants his testimony “done under duress.” Sentsov, applauding, shouts “Slava Ukraini! (Glory to Ukraine!)”, with Afanasyev answering back “Heroiam slava! (Glory to Heroes!).” The slogans, popularized by the Ukrainian Insurgency Army (UPA) during World War II, were adopted as a rallying cry of resistance on Maidan. It is doubtful that Sentsov was ever invested into Stepan Bandera, the far right wartime leader with whom the UPA was symbolically associated. Yet in refusing to be afraid, he can be seen as embodying a spirit of resistance that makes him a far greater threat than the terrorist that he is not. His parting words to Russians were telling: “We also had a criminal regime but we came out against it.”

#12

Askold Kurov: “Movies cannot change things, but they can change individuals”

Danyliw Seminar, 16 November 2018

https://www.danyliwseminar.com/askold-kurov

Transcript of the Q&A with filmmaker Askold Kurov that followed the screening of The Trial: The State of Russia vs Oleg Sentsov at the Danyliw Seminar on 16 November 2018. Questions and answers were edited for style by Sophie Foster. A few comments were added in brackets for context.

Born in Uzbekistan in 1974, Askold Kurov has lived in Russia since 1991. He co-directed in 2012 the award-winning documentary Winter, Go Away! His next films Leninland and Children 404 also won critical acclaim and screened at numerous festivals.

Question: Can you tell us more about how this film came to be? What is the origin of this film? Did you know Oleg Sentsov?

Askold Kurov: I met Oleg about three years ago, before he was arrested. Oleg had messaged me on Facebook, wanting to share his new film [Gamer]. I met him in person at his film’s premiere in Moscow. I became interested in this story when I saw how fake the case looked. I was discussing some ideas I had on the subject with a friend when he suggested that I make a documentary. Eventually, I felt that making a documentary would be the only way I could help.

How did you get funding?

I didn’t really have problems getting funding because I was the only cameraman shooting inside the courtrooms. The Russian legal system wanted filming within the courts because they wanted to make sure that the case looked legal and real. The funding aspect of this film took a long time, however, because we couldn’t get funding in Russia or Ukraine. We decided to use international Crowdfunding, where we found a Polish corporate user who got us in contact with Polish, Czech and Estonian film institutes.

Regarding the filmmaking process itself: You remained distant on the tensions within his family. Why have you decided to just mention it rather than thoroughly discuss it?

The story is really complex and it has multiple facets to it. Because Oleg is such a diverse person it was hard to give details on everything. Also, his family situation is a sensitive topic and it’s very hard for him. [His brother-in-law and nephew work for the Crimean FSB and he is estranged from his wife –Editor]

Can you talk about some of the difficulties in filming? What was the reality of filming the trial?

This film was difficult because it was my first [political] documentary. In my previous films I usually just follow characters and observe but in this film it was more than just observation; it included investigation, etc. At some points in the filming process we ended up using hidden cameras because we were not allowed to film. The most difficult part was when you knew that you were being followed. We also knew of instances where our cell phones were being tapped. I sometimes passed through moments of paranoia, where I was afraid all the time and I couldn’t sleep.

Where are we on the negotiations of exchange of the prisoners? Is there a possibility of exchange of the prisoners from Russian prisons? Can this movie help to cause an exchange?

I hope that this movie can help. Unfortunately, Oleg isn’t the only political prisoner; I don’t know the exact number but we’re talking about dozens of them. Many film festivals and even Amnesty International and activists are trying to organize screenings in order to invite politicians. It would be a big surprise if Oleg would be the next to be exchanged because the Russian legal system has its own logic and nobody knows how it works. A month ago we had an update on where Oleg is; it seems that they’re moving him from prison to prison and he is now in a place much closer to the North Pole. The conditions here are much tougher than where he was in originally. He is now facing problems with his health, specifically problems with his heart. We were hoping for some sort of exchange but not to change location for the purpose of tougher conditions.

Regarding the speech that Oleg gives at the end of the film, how did anyone allow him to say the things he was saying? Was his monologue on the state of Russia cut off at all? He’s placing himself with artists fighting the state. I wonder how aware he was of placing himself with Soviet artists? How aware was he that this filming was going out to a large audience? How much of this awareness help to shape the film?

There hasn’t been much of an interruption between Soviet Russia and the current Russia. It looks very much the same. I had some cooperation with Oleg but only through his lawyer and attorney. Through this cooperation I was able to get permission to meet his family and children. It was very important to Oleg that he knew what I was doing. Of course, Oleg had prepared all of his speeches during the trial. I think that it was very important to Oleg to have the ability to say something to a larger audience. In a way, he is a co-director of this film.

The last words in the trial are “Do not be afraid”. It seems you’re not afraid yourself… What have been the consequences for you?

Just to make a correction: He says the people should “Learn not to be afraid.”. I didn’t have any problems during the filming and I still don’t have problems with authorities or crossing borders. For instance, I didn’t face any issues coming to Canada. Maybe they just don’t really care about me? It’s not absolutely the same Soviet times in Russia at the moment. The borders are still open, there are at least a few medias and real newspapers, some internet and TV channels as well as some online media.

Has the film been shown in Russia? Or available? What has the reaction to it been?

It hasn’t yet premiered in Russia. We’ve tried but some film festivals refused to include it without an explanation. It’s not officially banned or forbidden, but the system sends you signals and you just have to choose what to do. I hope that in a week we’ll have news of an independent film festival in Russia if they’ll include the film. If they do we’ll include it and premiere it in Russia. Shortly after that, we’ll put it online on online forums.

Can you interpret the scene that comes early into the film? The scene where a couple of men light an entranceway on fire and then a different man extinguishes it, what was this meant to show and how was interpreted by the FSB officers? Also, how does Oleg feel Ukrainian? Was his family dismissive of his Ukrainians beliefs? Did that come up in your conversation with them?

This scene took place in Crimea, and the entranceway was an office of pro-Russian organizations used by the officers who detained pro-Ukrainian activists in Crimea. The two who lit the fire were normal guys, they were not military or police. They had information that these pro-Ukrainians were tortured there, so they tried to burn these places. It was out of protest. The FSB tried to use this to say that they were extremists and that they have a connection to a radical right organization and that Oleg was the leader of this organization. It’s very complicated but they basically tried to connect a lot of cases together in order to create this illusion of a big network.

Regarding the second question, this question of identity is new. Oleg was part of this new form of Ukrainian identity. His sister does not share this idea. His mother doesn’t like what happened after the annexation but she feels as though “she’s between two fires,” in her exact words. When editing the film, they decided to let her cousin [Natalia Kaplan, a main figure in the film –Editor] explain this complicated situation because I didn’t think it would be right to use the mother for the explanation.

When you’re showing the man who was identified as insane and who was a specialist in chemistry, and the scene where they’re testing chemicals in a wooded area; how did you get the material of those scenes?

This is the material of the FSB, it was just part of the case. I got the material from Oleg’s attorney as the scene was shown as evidence during the trial.

I noticed that Oleg called Putin a “Bloody Dwarf”. Almost every country has limitations on called leaders names. Can you comment on that? He’s making reference to Putin’s height I believe, which I would say is name calling, or bullying right?

When I was there during this trial, I didn’t feel that Oleg had crossed any boundaries. I think that sometimes calling names has a direct meaning. An artist’s task is calling names or to find the real names of a character.

First, why did the FSB choose Oleg as a mastermind in your opinion, was he already on a blacklist? Second, when are you planning to screen your movie in Ukraine?

We actually already had a premiere in Ukraine in March at a film festival [DocuDays, the leading documentary festival in Ukraine –Editor]. After that we had a release in the biggest cities in Ukraine, and we continue to have screenings from time to time.

I think from the very beginning that Oleg was a random victim. After, I realised that Oleg was in some kind of list because he had communications with Ukrainian activists in Maidan and had some activity with the Ukrainian military who were in Crimea. [He brought humanitarian assistance to soldiers trapped in their barracks –Editor] Oleg even tried to organize a rally against the annexation before the referendum. Of course, the FSB knew about him. Maybe they chose him because he was one of the most well-known persons in Crimea and it allowed the FSB to achieve multiple goals. They were able to stop Oleg as well as other activists. Many activists just abandoned their actions. This worked really well for propaganda, and they were able to use this case to prove there is a dangerous Right Sector in Crimea.

Your film makes a gruesome impression of what’s going on in Russia and the regime. How do you see the situation in Russia right now and did you get any support on the ground while making the film; any solidarity that wasn’t shown in the film?

In Russia, we had many activists who left Russia and went to Ukraine. Oleg’s cousin is an example of that. We are always waiting for something to help the political situation. You know that we had this protests movement in 2011 and then in 2012 we were so inspired. It looked like we just needed a little time to change everything and then nothing happened. After that, the system changed a lot in the political sphere and we had more and more political prisoners. In the spring, suddenly many young people went to the streets completely unexpectedly. Nobody knows why they suddenly appeared. I don’t know how and when but I hope that this regime will change quite soon.

What do you think about making movies to change the political system? You’re educating through movies but has anything really happened? What can art do?

I don’t believe that movies can change things but that movies can change individuals. These individuals are the ones who can change everything. I do believe that we must use art. We have one experience of Soviet times when one specific person was imprisoned. Many European artists tried to help him and only after a famous person said that he will only come to the Soviet Union once this prisoner is free did we see a chance. Maybe something similar will happen to Oleg.

In a sense this is a Russian film; it’s about the Russian justice system. It’s also Ukrainian, he identifies as Ukrainian. Central Europeans made this movie possible through funding, how do you explain that you couldn’t getfunding from Ukrainians?

As I explained to by a Ukrainian film producer, the economic situation was very difficult after Maidan and the only funding is state funding. All in all, I’m not sure why Ukraine didn’t give us money.

#13

Nationalist Radicalization Trends in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine

by Volodymyr Ishchenko

PONARS Policy Memo 529, May 2018

Volodymyr Ishchenko is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute.

Ukraine today faces a vicious circle of nationalist radicalization involving mutual reinforcement between far-right groups and the dominant oligarchic pyramids. This has significantly contributed to a post-Euromaidan domestic politics that is not unifying the country but creating divisiveness and damaging Ukrainian relations with its strategically important neighbors. The lack of a clear institutionalized political and ideological boundary between liberal and far-right forces lends legitimacy to the radical nationalist agenda. Moreover, the oligarchic groups exploit radicalizing nationalism not out of any shared ideology but because it threatens their interests less than the liberal reformers. Local deterrents are insufficient to counter the radicalizing trend; Ukraine’s far right vastly surpasses liberal parties and NGOs in terms of mobilization and organizational strength. Western pressure is needed on influential Ukrainian figures and political parties in order to help shift Ukraine away from this self-destructive development.

Mass Attitudes Versus Real Politics

There are two major narratives about nationalism in post-Euromaidan Ukraine: “fascist junta” and “civic nation.” The first was promoted by the anti-Euromaidan movement, pro-Russian separatists, and the Russian government. The “fascist” part is directed first and foremost at Ukrainian radical nationalists in the Svoboda and Right Sector parties, which were among the most active collective agents in the 2014 Ukrainian revolution. The “junta” part points to the unconstitutional removal of former president Viktor Yanukovych from office.

After the first Minsk agreements in September 2014, the “fascist junta” narrative disappeared from Russian media (though not from pro-separatist sources), reflecting Moscow’s official strategy of negotiation with, rather than removal of, the new government in Kyiv. Indeed, at the time, there was exaggeration of the influence of far-right groups and political parties, which ended up taking relatively marginal positions in the new government, performed poorly in the presidential and parliamentary elections, and left the government altogether after October 2014.

The opposing liberal-optimistic narrative posits that a “civic nation” has been emerging as a result of the Euromaidan and the war in Donbas. This new civic identity is allegedly inclusive of the country’s regions, cultures, and language groups. The main systematic evidence in support of this claim are various polls indicating an increase for “civic” rather than “ethnic” answers about Ukrainian identity.[1] However, the true nature of Ukrainian politics today is that it has been heading in the opposite direction.

The poor electoral performance of far-right parties in 2014 demonstrated that they were not capable of competing with the established political machines backed by oligarchic money and media. However, this ignores the growing—and unprecedented in contemporary Europe—extra-parliamentary power of the Ukrainian far right, which over recent years has been able to:

*Penetrate law enforcement at the highest positions;

*Form semi-autonomous, politically loyal, armed units within official law enforcement institutions;

*Develop strong positions and legitimacy within civil society, often playing a core role in the dense networks of war veterans, volunteers, and local activists.

Electoral performance is not a good measure of the influence of radical nationalists. Similarly, no one claims that Euro-optimist liberals hold a marginal position in Ukraine because of the poor electoral performance and low ratings of the liberal Democratic Alliance or People’s Power (Syla Lyudei). These two parties are arguably the only relevant ones that take the ideology seriously rather than opportunistically exploiting it to receive approval and support from Western elites and the Ukrainian electorate. One of the reasons for the far right’s poor electoral performance is that “centrist” oligarchic electoral projects exploited the issues, rhetoric, and slogans of the radical nationalists, thus shifting the political mainstream rightward.