Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

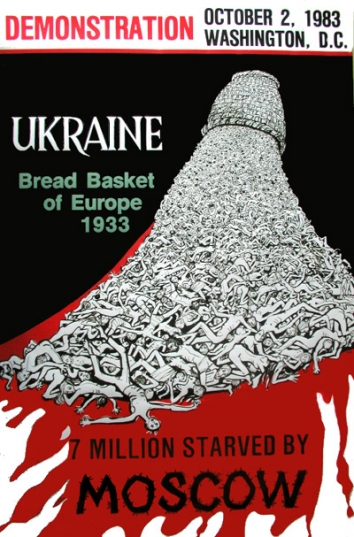

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

THE FREE WORLD....What it Achieved, What Went Wrong and How to Make it Right

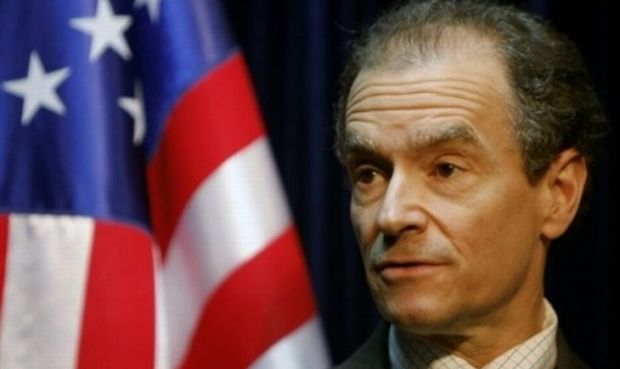

ESSAY by Ambassador Dan Fried, Distinguished Fellow,

Atlantic Council's Future Europe

Initiative and Dinu Patriciu Eurasia CenterAtlantic Council,

Washington, D.C., June 5, 2017

The_Free_World_web_0605.pdf

Once again, authoritarians are challenging the world’s leading democracies, using twenty-first century versions of aggression, propaganda, and subversion. The very notion of a rules-based, democratic-leaning international order—the Free World—seems in doubt, questioned also by newly-emboldened nationalists on both sides of the Atlantic.

In “The Free World,” Ambassador Dan Fried, who retired this year as the United States’ longest-serving diplomat, reminds us what the Free World achieved, where it has gone wrong, and what democratic forces can do to restore the momentum of ideas that still represent the best hope for American interests, democratic values, and the world.

----------------

ESSAY - THE FREE WORLD - Ideas have power, not all ideas and not under all circumstances, but the idea of a liberal world order demonstrated its power at two turning points: the resurrection of the West after World War II and the expansion of the West after the fall of Communism in Europe in 1989. The phrase “liberal world order” sounds like the invention of a political science seminar. It may be better to call it the Free World Order, as the Free World—its values, institutions, and purposes—remains the best organizing framework for humanity in the twenty-first century.

The principles behind the Free World have deep roots on both sides of the Atlantic. As the United States emerged as a world power at the end of the nineteenth century, it developed America’s Grand Strategy, which opposed the prevailing European spheres of influence and closed empires. In contrast, the United States sought a rules-based world, open beyond Europe to all nations, which would be more just and simultaneously play to our commercial advantage; in our massive self-confidence, we believed that our Yankee ingenuity would naturally prevail in fair competition.

We came to associate democracy and the rule of law with our interests. We understood that our nation would prosper best when other nations did as well; we believed we could build a better world and get rich in the process. We thus defined our national interest in broad, not narrow, terms and benefited accordingly. As it unfolded in the twentieth century, America’s Grand Strategy made us exceptional among the Great Powers, an object first of astonished frustration and later admiration among them.

Europe established the Free World’s intellectual foundations, but its road was darker. The notion of a just international order rooted in transnational values is at least as old as Erasmus; Kant developed a theory of perpetual peace between states committed to the rule of law and republican values.

But, Europe’s Great Power rivalries led to one world war; the subsequent rise of two aggressive, anti-democratic ideologies generated a second. By 1945, with continental Europe in ruins and Stalinist power seemingly on the rise, Europe and America set out to build the Free World.

Though we now take them for granted, the results deserve review: the Soviet Union was contained at the line of 1945; Western Europe was secured and then grew prosperous, its politics stabilized; and Europe’s national fratricide gave way to transnational cooperation through the creation of NATO and what became the European Union (EU). The achievement of the democratic West inspired the dissidents in Soviet-controlled Europe; when Communism fell in 1989, the self-liberated nations of Central and Eastern Europe clamored to join the West’s Free World.

The West responded, and its great institutions, NATO and the EU, grew to embrace another 100 million Europeans. For all the shortcomings, blunders, inconsistencies, and failures of the Free World—and America had its share—the West has enjoyed its longest period of general peace since Roman times, and the greatest ever period of mass prosperity and democratic governance.

On June 5, 1947, in response to the devastation of World War II, George Marshall announced an unprecedented American commitment to help rebuild the economies and spirits of Europe. That speech became known as the Marshall Plan: a US strategy to promote European cohesion and prevent another world war. It was based on an understanding that American security and prosperity were sustainable only if shared; the United States and Europe would stand, or fall, together.

June 5, 2017, marks the seventieth anniversary of the Marshall Plan and offers an opportunity to reflect on the successes of the Marshall Plan in catalyzing Europe’s economic recovery, the formation of the North Atlantic alliance and eventually the European Union, and over seventy years of general peace and prosperity in the West. The Council’s team views this seventieth anniversary as an opportunity for the transatlantic community to recommit to the values and the spirit captured by George Marshall and America’s broad vision of our interests.

[1] WHAT WENT WRONG?

But if it was so good, why the present self-doubt? What explains Brexit and the rise of nationalist politics in Europe and America? What has gone wrong?

As was the case in the 1930s—another period of Western demoralization— economic distortion generates a political counterpart. We might have expected a political reaction after years of slow growth and high unemployment in Europe, especially youth unemployment, following the panic of 2008. We should not have been surprised by so many Americans recoiling in the face of hard times and gilded-age levels of income inequality. The perceived failures of government—European and American—to address these issues has led to political alienation and bitterness.

In the United States and perhaps the United Kingdom, the Iraq War also fed this sense. Add to this challenges of national identity in the face of high immigration—Latino in the United States, Middle Eastern and North African in Europe, Eastern European in some parts of the UK—which historically has generated nativist hostility.

In response, the United States and EU seem to have fallen short. In Washington, “faction,” the Founders’ term for partisanship, has paralyzed critical aspects of governance. In Europe, the EU has failed to establish a connection with Europeans; for many, “Europe” remains an abstraction. There are EU institutions with real power, with proven capacity to think and act in strategic terms. But there is no real Europe-wide political constituency.

Rather than functioning as a polity with a democratic mandate, the EU often feels more like a multilateral organization whose leaders are chosen by inside brokering. Europe and America thus suffer from different forms of democratic deficit: Europe because of institutions that seem unlinked to democratic politics and are weaker for it, and the United States due to institutions captive to partisanship that sometimes barely function.

In addition, Russia is again acting as a corrosive political spoiler, malign by intention, using propaganda, corrupt funding, and other active measures updated for the cyber age. Its objective is the same as in the Soviet period: to weaken the West’s institutions and discredit Western values, thus shielding Moscow’s despotic system from liberal influence and easing Russia’s domination of its neighbors…

NOTE: THE FREE WORLD ESSAY: To read the entire essay, please open an attachment or follow the link below:

NOTE: Ambassador Daniel Fried is a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative and Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. In the course of his forty-year Foreign Service career, he played a key role in designing and implementing American policy in Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union.

As special assistant and NSC senior director for Presidents Clinton and Bush, ambassador to Poland, and assistant secretary of state for Europe (2005–09), Ambassador Fried crafted the policy of NATO enlargement to Central European nations and, in parallel, NATO-Russia relations, thus advancing the goal of Europe whole, free, and at peace. During those years, the West’s community of democracy and security grew in Europe.

Ambassador Fried helped lead the West’s response to Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine starting in 2014: as State Department coordinator for sanctions policy, he crafted US sanctions against Russia, the largest US sanctions program to date, and negotiated the imposition of similar sanctions by Europe, Canada, Japan and Australia.

=========================================================

U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC)

1030 15th Street, N.W., Suite 555 W, Washington, D.C.

Morgan Williams, mwilliams@usubc.org; www.USUBC.org; 202 437 4707

===========================================================

Power Corrupts & Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely.