Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

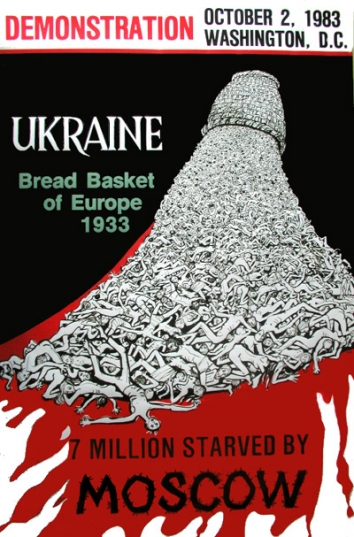

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

SEIZING RUSSIA’S FROZEN $300 BILLION

IS LEGAL, URGENT AND RIGHT

Vladimir Putin’s attack against Ukraine is also an assault erga omnes, “toward all.” Remember that term – the future of international law hinges on it.

Vladimir Putin’s attack against Ukraine is also an assault erga omnes, “toward all.” Remember that term – the future of international law hinges on it.

Op-Ed by Andreas Kluth

Bloomberg, New York, NY

Thu, Feb 15, 2024

Putin must pay. Photographer: Fadel Senna/AFP via Getty Images

“This case is the gravest test for the future of international law since the creation of the United Nations.” So I’m told by Philip Zelikow, a former US diplomat now at Stanford University (who earned kudos in 2004 as lead author of the 9/11 Commission report). What’s at stake, he says – and I agree – is whether the UN, in the face of Russian aggression against Ukraine, will stand up to crimes against humanity or go the way of the League of Nations when it failed to restrain Mussolini and Hitler. More succinctly: Will we advance international law or let it become irrelevant?

The immediate question is whether countries that hold currency reserves owned by the Russian central bank may legally confiscate that money and give it to Ukraine as war reparations. This concerns about $300 billion worth of assets held in Belgium, France, the US and other places, and frozen since Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded two years ago and began committing war crimes.

So far, scholars, politicians and pundits – including me – have been coy about transferring the Kremlin’s sovereign cash to Kyiv. The UN Security Council – in which Russia wields a veto – has passed no resolution that would allow it. And international customary law (the body of accepted practice among states) seems to frown on confiscation. While it explicitly allows “countermeasures” against aggressors such as Russia, it’s the victim – in this case, Ukraine – that should take them. Well, a lot of those scholars and pundits, again including me, took an overly narrow view of customary law.

That’s what Zelikow and a large cohort of international lawyers from countries across the world plan to argue in an open letter next week, around the second anniversary of Putin’s invasion. They’re drawing attention to the cumulative work of the International Law Commission, birthed by the UN General Assembly in 1947 to develop and codify international law, and especially the customary kind. (Think of treaties as the equivalent of statutes in domestic law, and customary law as the analog of case law.) The commission has put out tons of work over the decades, including the Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts.

The articles don’t amount to a treaty (like the Geneva Conventions, say). But they’re an accepted guide to international customary law, which the International Court of Justice in The Hague has cited as authoritative. For example, they’re the basis on which South Africa, a third country, has “standing” before the court to accuse Israel of committing genocide in the Gaza Strip.

Unsurprisingly, the articles on responsibility have a lot to say about the countermeasures Ukraine may legally take against Russia. But the text is also clear that Russia – by causing international refugee, food and security crises – has hurt many other countries too, and that these states are equally within their rights to respond. Crucially, moreover, the articles stipulate that some atrocities are so grave that they amount to attacks on the international community as a whole. In the technical phrase, these crimes, including genocide and wars of aggression, amount to assaults “toward all” – in Latin, erga omnes.

These situations permit any and all states to take countermeasures and seek redress. Does Putin’s invasion fit the description? The UN General Assembly has condemned it in three resolutions, and the court in The Hague has ordered measures against Russia – all of which Putin has ignored. Yes, the International Law Commission’s code is written with crimes like the Kremlin’s in mind.

So where do we go from here? I think individual countries passing national laws to seize the Russian assets – as the US Congress is trying to do with the so-called REPO for Ukrainians Act – would set a bad example. It introduces arbitrariness, and would encourage cynicism in other countries, notably China, and efforts to hold foreign reserves in politically friendly countries and currencies other than dollars or euros. Better, therefore, to stick to international law all the way.

Zelikow and his co-authors pay particular attention to a resolution by the UN General Assembly that calls for setting up “an international mechanism” to pay reparations to Ukraine. Countries would place Russia’s sovereign assets into an escrow account administered by an international body. It would then allocate the money to compensate Putin’s victims and rebuild Ukraine.

Such measures obviously wouldn’t solve all of Kyiv’s problems. The Ukrainians are fighting for their national existence, and the Russians have an advantage of three to four times in the production of ammo, according to Estonian estimates. Continued aid from the US seems deadlocked in Congress. And even if Russia’s sovereign assets are confiscated, they can’t be used to pay for guns and shells. But money is fungible. So every dollar taken from the Russian central bank and spent to rebuild a Ukrainian power plant or hospital frees up a different dollar Kyiv can spend on its army.

More importantly, the international community would send a signal that it’s determined not to fail this time as it did in the 1930s. It will set a precedent which says that the aggressor pays. Two years into Putin’s atrocities, the world must assert justice – by enforcing the letter and spirit of international law.

NOTE: Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.