Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

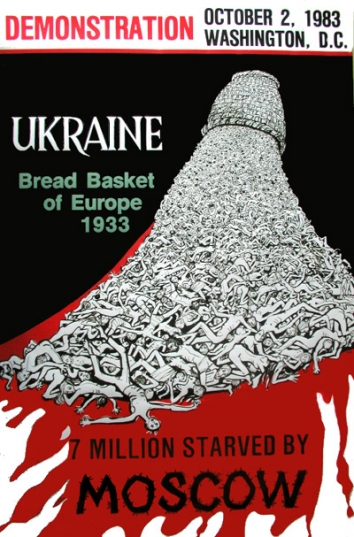

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Saving Ukraine’s Economy:

the Grain Giant Fighting for Survival

Nibulon helped turn the country into the ‘breadbasket of the world’. The Russian invasion has brought it to its knees

Nibulon helped turn the country into the ‘breadbasket of the world’. The Russian invasion has brought it to its knees

John Paul Rathbone and Ben Hall

Financial Times, London, UK, Wed, Mar 22, 2023

Andriy Vadatursky, chief of Nibulon, one of Ukraine’s biggest agro-industrial companies

© FT montage: Nibulon/Bloomberg

Before they were pushed out by Ukrainian troops, the Russian soldiers scrawled “BOOM” in garish red lipstick across the laboratory table in the Nibulon grain terminal.

They ransacked offices at the company’s partially destroyed Kozatske facility, which lies on the west bank of the Dnipro river in southern Ukraine. They even destroyed the flower beds planted outside.

“Before the war we built silos, roads, a fleet of ships, all with Ukrainian steel . . . Ukraine had one of its best harvests ever,” recalls Andriy Vadatursky, Nibulon’s chief executive and scion of the family that owns the Ukrainian grain company.

“After the war, everything stopped,” he continues. “The Russians are trying to destroy ports, the energy system . . . and of course the flow of grain.”

No individual can encapsulate the whole bloody story of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. But Nibulon, one of Ukraine’s biggest agro-industrial companies, comes close.

As a pioneering company that helped develop Ukrainian agriculture into a world leader, it is also an example of how the Russian invasion has thwarted the country’s economic potential and undermined its ability to sustain the war and establish itself as a thriving democracy.

The 92,000-tonne Kozatske silo (inset above) — still shelled periodically by the Russian troops that retreated across the river last autumn — was one of 22 where Nibulon once collected millions of tonnes of grain every year. It then shipped the grain downriver in company-made steel barges to the port of Mykolayiv, and loaded the cargo into bulk carriers bound for global markets.

It was a logistics chain that helped remake post-Soviet Ukraine as the “breadbasket of the world” and turned Nibulon into one of its most successful companies. It made the company’s founder, Oleksiy Vadatursky, an estimated $430mn fortune and won him the “Hero of Ukraine” award, which pro-European president Viktor Yushchenko bestowed in 2007.

It also singled him out as a high-value Russian target. Last summer, Oleksiy, 74, and his wife Raisa were killed in their Mykolayiv home amid a volley of Russian missiles. At the time, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy described his death as “a great loss for all of Ukraine”. Nobody else was killed in the attack on the city that night, and senior officials intimated it had been a deliberate assassination.

“I remember every minute of that day,” says Andriy, Oleksiy’s only son, who suddenly had to assume control of the company. “My father and mother were killed on July 31. I became chief executive on August 4. On the fifth I held his funeral and had to make sure we had enough money to pay employees their salaries.”

Russia’s invasion has spawned many casualties: an estimated 100,000 Ukrainian soldiers killed or wounded, 30,000 civilians dead, 8mn refugees and another 5mn displaced within the country. But in addition to this human toll, the conflict has devastated the Ukrainian economy and its companies.

Last year, the economy shrank by 30 per cent and unemployment hit 35 per cent. Over three-quarters of companies stopped or scaled back production. Repeated Russian missile attacks on Ukraine’s electricity system hammered output just as it was beginning to recover.

The end of winter and better power supplies have now stabilised business sentiment, although at a low level, according to the central bank. “We’ve passed the critical point,” says Oleksandr Gryban, deputy economy minister. “We’re becoming safer against economic disruption.”

Even so, Ukrainian companies still face an uphill struggle. Many are cutting production and staff. Interest rates stand at 25 per cent, squeezing domestic lending. Non-performing loans in the banking sector stand at 38 per cent. They have risen fastest among large companies and those with foreign currency loans, says Nataliia Shapoval, director of the Kyiv School of Economics Institute.

People pay their respects to Ukrainian agricultural magnate Oleksiy Vadatursky and his wife Raisa before a funeral service in the St Volodymyr Cathedral in Kyiv in August last year. © Genya Savilov/AFP/Getty Images

That is because Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea has choked off their main export routes, and a UN-sponsored deal, which has allowed 25mn tonnes of grain to leave certain ports, has only provided partial relief. In 2019-20, the sector exported 55mn tonnes of wheat, corn and barley.

Other large agricultural companies have struggled. The war pushed both grain exporter Kernel and poultry grower MHP to what credit ratings companies consider the brink of default, though Kernel has since bounced back. As for Nibulon, which owes a total of $570mn to 26 western and Ukrainian creditors, it stopped paying its international lenders last autumn.

“People talk a lot about military support and how people are suffering. But nobody is talking about companies,” says Vadatursky. “I’m worried that in the bigger picture, business will not survive. And business is fundamental to every country.”

RISE AND FALL

Oleksiy Vadatursky was an entrepreneur who fully understood how fundamental business is to a country’s sense of wellbeing.

Known in Kyiv as “Old Man River”, with a shock of white hair and a physique that looked like packed concrete, he grew up on a collective farm. In 1991, the year of Ukraine’s independence, he also had a brilliant entrepreneurial vision.

The then 42-year-old sought to build a farming-cum-logistics-cum-shipbuilding conglomerate based out of a Soviet ship building plant in Mykolayiv. His central idea was to turn the Dnipro into an agricultural logistics artery similar to the Mississippi in the US.

While Ukrainian oligarchs made billions in the post-Soviet years through state capture and graft, Vadatursky built his empire with the aid of loans from a range of public and private financial institutions both in Ukraine and abroad.

“There are many different gradations of odiousness in Ukrainian businesses, but at the good extreme were people like old man Vadatursky — a Soviet man, tough as nails, but with a heart of gold, who showed you could set up a clean business,” says Daniel Bilak, head of international law firm Kinstellar’s practice in Kyiv.

At the time, Ukraine was barely self-sufficient in food. In the early 2000s, its grain harvest even dropped as low as 20mn tonnes. By 2021, however, the national harvest had tripled to almost 60mn tonnes, and the sector employed 14 per cent of the population and accounted for a third of national economic output.

Oleksiy became a wealthy tycoon, commanding a fleet of 82 vessels and over 76,000 hectares under cultivation. But his entrepreneurial vision also benefited the wider region, and his reputation was further burnished for keeping Nibulon in Ukraine, instead of moving it to lower tax jurisdictions offshore, and for his large investments in the area.

Nibulon also shipped grain for 4,500 private farmers at farm-to-ship transport costs as low as $5 a tonne. And as a third of Ukrainian grain exports moved through Mykolayiv, the port and Nibulon’s operations there boomed.

“He was the father to [Nibulon’s] 6,000 employees,” Andriy Vadatursky says.

Then the Russians invaded. Troops occupied nearby Kherson, and shelled Mykolayiv daily for nine months — including the salvo of missiles that killed Oleksiy last July.

The laboratory at the Nibulon grain terminal in the Ukrainian port of Mykolayiv that was damaged and defaced by Russian forces © Nibulon Press Service

None of Mykolayiv’s former bustle was evident on a recent visit. Boarded-up barges and tugboats were moored at the quay. Seabirds whirled around buildings half-destroyed by missiles. And enemy troops occupying the Kinburn Spit across the estuary still occasionally launched attacks, including on a Nibulon boat in November.

“Many of our big companies have been destroyed and are not coming back yet — the military risks are too big,” says Vitaliy Kim, governor of the Mykolayiv province, sitting in an improvised office after a Russian missile destroyed his former office in city hall. “The big problem is jobs.”

Local companies have done their best to adapt. Agrofusion, Europe’s third-biggest maker of tomato paste, has used mobile homes to house workers who lost their homes to the war. Despite its shattered greenhouses, it restarted some operations last month, according to Kim.

Nibulon has meanwhile had to reinvent its logistics chain, as have all of Ukraine’s grain companies. With no access to the Black Sea and much of the Dnipro off limits, the invasion pushed up transport costs to over $150 a tonne, Vadatursky says.

The company has since built a terminal at Izmail on the Danube that ships around 240,000 tonnes a month. That has helped reduce transport costs to around $125 a tonne. Even so, from a record 5.6mn tonnes in 2021, Nibulon’s exports dropped last year by two-thirds to 1.8mn tonnes.

Mines and unexploded ordnance are another problem. Mykolayiv was almost captured in March as Russian forces tried to push towards Odesa, and the roads out of town are flanked by trenches and run through artillery-pocked fields overlooked by concrete pillboxes.

At an agricultural plant in Snihurivka, a small town some 40km from Mykolayiv that once stood on the frontline, equipment hangars and grain silos have been shot to pieces, the tarmac is charred by gunfire, a dormitory village has been all but abandoned, and uneasy Ukrainian troops stand guard.

“Over a third of buildings are completely destroyed, 95 per cent are damaged, there is no electricity and there is no water. We live off aid,” says Alexander, a town spokesperson. “Few people have come back, and anybody living here is a bit mad.”

He gestured at thin strips of roped-off land that have been demined so repairmen can fix the overhead electric cables.

“They say every month of war requires a year of demining. So that means it will take nine years to demine here,” Alexander says. “Will people come back? Maybe never.”

ECONOMIC LIFE SUPPORT

With as much as a quarter of Ukraine’s 40mn hectares of arable land in need of demining, removing unexploded munitions may be the most dangerous task facing agricultural companies such as Nibulon. But Vadatursky’s most pressing need is cash — he calls it “oxygen” — to tide the company over the war.

The Nibulon chief executive wants a negotiated debt standstill that will give the company financial breathing space. But an attempt to agree a debt rescheduling agreement with international creditors has stalled. Some Ukrainian banks have even started to seize the company’s assets.

To get finance flowing again, Vadatursky wants Ukraine’s western allies to provide guarantees covering war risks so that private and multilateral development banks can lend to Ukrainian companies.

Deputy economy minister Gryban says a top priority for Kyiv is persuading Ukraine’s G7 allies to create a trust fund to cover reinsurance costs for private lenders. So far, though, only a few tens of millions of euros have been made available to cover war risks in Ukraine, provided by the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

As for direct investment, the World Bank’s private lending arm, the IFC, has earmarked $2bn to help Ukrainian businesses, but there has been no government compensation for business losses. Meanwhile private capital remains leery of investing in a war zone. Corruption, particularly in the judicial system, also remains a big deterrent to new investment.

Those still willing to invest are seeking what Vadatursky calls “criminal” knockdown prices. “Ukrainian assets are very cheap, so of course, there is interest to buy,” he says. “The question is whether it’s a good time to sell.”

Tomas Fiala, chief executive and founder of Dragon Capital, a Kyiv-based investment bank and asset management company, concurs.

“Private equity firms and other foreign investors are certainly looking and using this time to raise funds,” he says. “But although people are very sympathetic, 95 per cent of that money won’t be invested here until the war is over.”

One hope is that a successful Ukrainian military offensive this spring will bring the end of the war closer by pushing out the Russian invaders, perhaps via a southern attack which severs the territory connecting the Russian mainland to Crimea. That could help end Russian control of the Dnipro and allow companies such as Nibulon to use the river as a logistics artery again.

Another big advantage would be if the UN-brokered grain initiative, which has enabled 25mn tonnes of grain to be exported from some of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, is eventually expanded to include the port of Mykolayiv and Nibulon’s facilities there. The agreement was extended on March 18, but no new ports were added.

Nibulon’s future “depends very much on the grain corridor”, says Gilles Mettetal, former director of agribusiness at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and now a member of Nibulon’s international advisory board. “Nibulon can self-finance itself if it achieves a certain level of exports.”

SUCCEEDING OLD MAN RIVER

As if this uncertainty was not enough, Vadatursky must also deal with the corporate legacy of his celebrated father, all the while reassuring nervous employees. It is a difficult balancing act.

Forty per cent of the company’s prewar staff cannot work because they joined the army, live in Russian-occupied territories or have moved away. But Vadatursky says he still seeks to “pay people their salaries, not to fire them, and save the team”. Around 80 per cent of Ukrainian companies say the same, according to central bank surveys.

At the same time, though, Vadatursky needs to move the company on from the management style of his father, which tended towards the patriarchal.

Andriy Vadatursky, Nibulon’s chief executive, assumed control of the company when his father was killed

© Julia Kochetova/Bloomberg

He has appointed an international advisory board, and divided the company’s main functions — agriculture, logistics, grain trading and shipbuilding — into separate profit centres. These are the kinds of modern, transparent corporate practices that Ukraine needs to adopt across the board if it is to attract foreign investment and integrate into European markets after the war.

First, though, Vadatursky needs to deal with his creditors. With a debt payment holiday and cash in hand, he says, Nibulon could finance next year’s crop, independent farmers would skirt bankruptcy, food would grow, Ukraine would need less western aid, and consumers across the world would get cheaper food.

“Without money, you cannot do anything,” he says. “It is my number one priority.”

Cartography by Cleve Jones

LINK: Saving Ukraine’s economy: the grain giant fighting for survival