Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

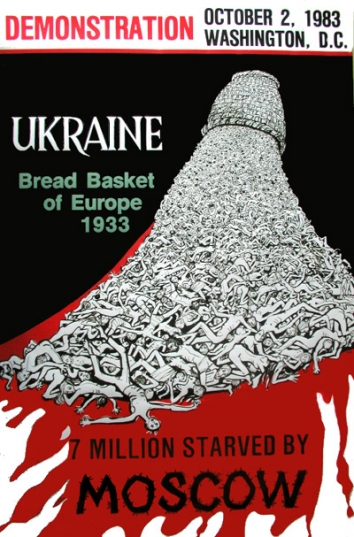

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

One Overlooked and Easy Way the Trump Administration Can Help Ukraine

By Anders Aslund, Resident Senior Fellow,

By Anders Aslund, Resident Senior Fellow,

Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center, Atlantic Council,

Thu, March 15, 2018

US President Donald Trump shakes hands with Ukraine's President Petro Poroshenko in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, June 20, 2017. Mykola Lazarenko/Ukrainian Presidential Press Service/Handout via REUTERS

Diplomatic relations between the United States and Ukraine are eminent. As former US Ambassador to Ukraine Steven Pifer writes in his new book, The Eagle and the Trident, they have almost always been good. Ukraine’s outstanding sacrifice was to give up the third largest nuclear force in the world.

An unfortunate consequence was that Russia started a war of aggression against Ukraine in 2014, annexing its southern peninsula of Crimea and occupying part of eastern Ukraine with irregular Russian troops. The United States responded with limited military supplies and eventually lethal weapons.

But the United States should do more for Ukraine. Now is the time to launch negotiations on a US-Ukraine Free Trade Agreement (FTA). Ukraine needs to enter new markets. It has suffered tremendously from Russian trade sanctions, which have slashed trade between Russia, its main trade partner, and Ukraine by no less than 80 percent from 2012-16.

Currently, Ukraine is going through a fast restructuring, boosting its trade with Europe to 40 percent of its total trade last year. Still, the Ukrainian economy is small—only 0.5 percent of the US economy and its total exports are just 1.9 percent of US exports. Therefore, the United States need not fear any trade shock from Ukraine.

Ukraine is most interested in new bilateral FTAs and would welcome one with the United States. Recently, it has concluded two big FTAs. In 2014, it did so with the European Union. It came into force on September 1, 2017. In July 2016, Canada and Ukraine concluded their FTA (CUFTA), and after their parliaments had ratified it, it came into force on August 1, 2017.

Barack Obama’s administration was not interested in bilateral FTAs. Toward its end, it nurtured two major regional FTAs, the Transpacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which have both been abandoned by Donald Trump’s administration. Instead, the Trump administration favors FTAs with individual countries.

The case for a bilateral US-Ukraine FTA appears obvious. The countries are friends, and both appreciate bilateral FTAs. Their bilateral trade is tiny but the United States enjoys a large surplus. The US Trade Representative reports: “Ukraine is currently our 81st largest goods trading partner with $1.7 billion in total (two way) goods trade during 2016. Goods exports totaled $1.1 billion; goods imports totaled $578 million. The US goods trade surplus with Ukraine was $499 million in 2016.” This tiny trade can develop to the benefit of both nations but hardly to the irritation of anybody. Most of all, a US-Ukraine FTA would be a gesture of friendship and solidarity against Russian aggression.

USTR continues: “The top export categories...in 2016 were: mineral fuels ($210 million), vehicles ($176 million), machinery ($175 million), aircraft ($91 million), and iron and steel products ($55 million). US total exports of agricultural products to Ukraine totaled $37 million in 2016.”

On the US import side: “The top import categories...in 2016 were: iron and steel ($258 million), electrical machinery ($39 million), inorganic chemicals ($27 million), iron and steel products ($27 million), and dairy, eggs, honey ($24 million). US total imports of agricultural products from Ukraine totaled $77 million in 2016.” These small volumes can hardly scare any protectionist. US foreign direct investment in Ukraine was $618 million in 2016, while Ukrainian investment in the United States was minuscule.

Canada’s free trade agreement suggests the kind of agreement the United States would like to have with Ukraine. Unlike Ukraine’s EU agreement, CUFTA is newly negotiated and fully modern. It contains rules of origin and trade facilitation, as well as rules for e-commerce, intellectual property rights, labor standards, and environment. Energy, agriculture, infrastructure, and technology are covered, while services and investment are excluded. Canada claims to have opened up 98 percent of its market to Ukraine. Tariffs are to be phased out gradually within 3-7 years.

Canada has set a useful example, though it might be advantageous if a US-Ukraine FTA included investment, given potentially large US investment in Ukraine. The United States and Ukraine already have a bilateral investment treaty of 1994, though it is rather rhapsodic and could benefit from an update, in particular, to include intellectual property rights.

The EU free trade agreement with Ukraine appears less applicable. It is not only an FTA but also an Association Agreement with broader political implications. While the negotiations of the CUFTA started in 2015, the EU Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement was negotiated from 2007, making it less up to date.

This is a propitious time for the United States and Ukraine to start negotiations about a bilateral free trade agreement.

Anders Åslund is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington and author of the book “Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It.”